Google, Mobile Search And The Paradox Of Competition

How much does Google figure into the “future of search,” whose advances will largely be determined by mobile and non-traditional devices? That’s a hard question to answer. On the one hand Google is one of the biggest (if not the biggest) brand in the world, with almost unlimited resources to develop technology or buy companies […]

On the one hand Google is one of the biggest (if not the biggest) brand in the world, with almost unlimited resources to develop technology or buy companies it sees as threats. (Google Ventures has for example invested in Expect Labs, which is building a next-generation mobile search capability.) On the other hand its traditional search model and content presentation are not well suited to a range of new search and discovery scenarios that are emerging. No one wants to see a traditional Google SERP on car-dashboard screen, for example.

If Google has its way it will still be central to the way consumers retrieve information for decades to come, on all manner of devices and in all manner of contexts: PC, TV, mobile, tablet, in-car, wearable, kiosks and so on.

Google is quickly trying to counter threats to its business in several ways even as it experiments with new technologies and search scenarios (e.g., Google Glass). For example, its revamp of voice search and expansion of Google Now is partly a response to Apple’s Siri and the rise of virtual assistants. And the fact that users can now obtain their airline boarding passes on Google Now is mostly a response to Apple Passbook.

This morning the NY Times has a general overview of mobile search and how mobile apps are offering new competition to Google. The article asserts that part of the reason Google escaped the FTC’s wrath on “search bias” is because the search market is evolving too rapidly — in the mobile arena. While that’s true, as the article points out, Google is more dominant on the “mobile web” than on the PC.

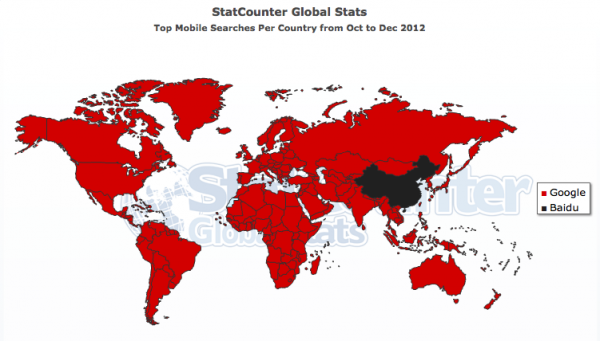

As the chart above reflects, outside of China, Google “owns” browser-based mobile search. It has a 95.8 percent share of mobile web search globally and only slightly less in the US. Most of mobile ad revenue is in search and almost all of it is Google’s.

Google’s success in mobile search is due in part to its aggressive mobile development efforts but much of it is Android. Android, controlled by Google, is now the world’s leading smartphone platform. Android is to iOS as Microsoft Windows was to Apple in the 1990s. This analogy has now been made so many times it’s almost a cliche. However Google Chairman Eric Schmidt himself recently used it.

If the FTC missed the boat it wasn’t on PC “search bias,” it was on exploring the relationship between Google, Android, mobile search and mobile advertising. However the Europeans have yet to conclude their inquiry, which does reportedly include Android.

As I’ve argued before, if Android continues to increase its share, it’s not inconceivable to imagine that regulators could ask that it be spun out of Google and made into an independent entity. The question is: how high would its share have to get before that might happen?

Notwithstanding the success of the iPhone 5 Google/Android is rapidly closing in on a 60 percent smartphone market share globally. And outside of China almost every one of those Android devices is a Google search device that helps generate ad revenue and reinforce Google usage. Google’s products are increasingly integrated an all support and reinforce “the Google habit.”

Google said on its last earnings call that it now had an $8 billion mobile “run rate.” That includes more than ads but the “vast majority” of that revenue is advertising and mostly search. Google has executed in mobile brilliantly and almost flawlessly. Even the “maps debacle” on iOS has resulted in a new and improved Google Maps app that is more well-liked than the old, pre-Apple Maps experience.

Yet Google remains vulnerable. Mobile apps give consumers direct access to content, making Google unnecessary in many cases. Yelp, TripAdvisor, Amazon, OpenTable, Kayak, NY Times, BBC, Hulu: all of these can be directly accessed via apps. And personal assistants such as Siri sit “on top” of Google in the same way that Google sits on top of publisher content on the PC internet.

On the PC Google was and arguably still is the most reliable way to navigate to sites or retrieve information when sources are unknown. However what consumers ultimately want is not Google itself (except in the case of Maps and a few other areas) but content, “answers” or specific information. Recognition of this is partly what’s driving Google to acquire more content (ITA, Frommers, Zagat) and to provide more vertical content and “answers” (Knowledge Cards) instead of traditional links: it’s what consumers want.

Indeed, Google’s mobile and smaller tablet search experiences push third party links below the fold in an increasing number of instances. Third party links become secondary options after Google’s “own content.” It’s strange to me that groups like FairSearch.org focused almost exclusively on the PC experience when mobile presents what is probably a more viable antitrust argument against Google.

For its part, Google is trying to straddle its traditional function (sourcing third party information) and its new function on mobile devices (getting people “answers” more quickly). As it does that it’s trying to manage and accommodate its old user experience and UI to the demands of new devices. At the same time it’s trying to not create too many different UIs and user experiences on different devices.

This is all a challenging balancing act but one that Google seems to be pulling off so far.

Yet even as Google asserts its dominance in browser-based mobile search it confronts a new group of search-insurgents (e.g., izik/blekko, Grokr, KickVox, Facebook Nearby, others) trying to offer richer experiences on mobile devices. It also contends with consumers increasingly directly accessing vertical content via mobile apps.

Who will win? It’s hard to bet against Google but it’s equally hard to imagine Google search hegemony into the indefinite future.

For the past several years the “future of search” was a murky thing, mostly dominated by Google in its present form. Now mobile devices, “ambient awareness,” big data and natural language processing (all of which Google is into) are starting to shake up the market and offer the possibility that search of the future looks almost nothing like the PC search of the past.

Postscript: It was pointed out to me that the FTC apparently did look into mobile competition and related issues in rendering its antitrust decision regarding Google. Here’s the relevant portion of the FTC’s letter announcing the conclusion of its inquiry:

The FTC also conducted an extensive investigation into allegations that Google biased its search results to disadvantage certain vertical websites; and that Google entered into anticompetitive exclusive agreements for the distribution of Google Search on both desktop and in the mobile arena. The agency decided not to take action in connection with these allegations.

Opinions expressed in this article are those of the guest author and not necessarily Search Engine Land. Staff authors are listed here.

Related stories

New on Search Engine Land