Could Google Play Jeopardy Like IBM’s Watson?

Like many people, I was amazed to watch IBM’s Watson supercomputer playing Jeopardy this week against past human champions. But could Google have done the same thing? Let’s go behind the scenes of these two search masters to understand what they can — and can’t — do. Which Clue Should I Take? Watson has been […]

Like many people, I was amazed to watch IBM’s Watson supercomputer playing Jeopardy this week against past human champions. But could Google have done the same thing? Let’s go behind the scenes of these two search masters to understand what they can — and can’t — do.

Like many people, I was amazed to watch IBM’s Watson supercomputer playing Jeopardy this week against past human champions. But could Google have done the same thing? Let’s go behind the scenes of these two search masters to understand what they can — and can’t — do.

Which Clue Should I Take?

Watson has been programmed to play Jeopardy. That doesn’t mean just being stuffed with millions of possible answers. It means that Watson has been taught the game’s strategy.

Watson has been taught to go for where Daily Doubles are likely to be. It knows to go for the lowest value clues in a topic to build confidence for future questions in that category. It uses bid strategies on how much to risk. IBM explains more about this in these posts below:

Google knows none of this. Google couldn’t play Jeopardy because despite knowing answers to many questions, it literally doesn’t know how to play the game. But potentially, researchers at Google could write their own game-playing software, if they wanted to try for the type of PR bonanza that IBM is enjoying right now.

How Do They “Hear” The Clues?

For either Google or Watson to answer a question, the first step is for them to receive it, to “hear” it in some way. Anyone who has used Google knows the way it hears most of its questions. People type them into a search box.

The same thing is happening with Watson. Behind the scenes, the question that Alex Trebek has asked is sent in text form to Watson. Presumably, all of Trebek’s questions have already been scripted, ready so the right question can be sent. Otherwise, Watson would be slowed by a human having to type in the question on the fly.

For more about Watson and how it receives questions, see this post from IBM:

What you might not realize is that Google receives a large number of its questions by voice. Many people speak their questions into applications on Android phones or the iPhone, for example. Google literally hears these questions, then uses software to turn them from voice into text. All this happens within seconds, and Google sends back an answer.

In this way, Google is actually more advanced than Watson. It can — and does — regularly respond with correct answers being asked in natural language, as spoken into phones.

What Did The Question Mean?

Hearing the question is only the first part of coming up with an answer. Next, you have to know what the question means. For example, take yesterday’s Final Jeopardy question:

Its largest airport is named for a WWII hero. Its second largest for a WWII battle.

Chicago was the answer, of course — not Toronto, as Watson mistakenly replied.

A human being will understand that this question is about a city, because a human will know the entire context of the question — cities have airports. A human also understands that “second largest” is a reference back to the first sentence — that another airport is being discussed, even if that’s not explicitly said.

Those are just two examples of where a human can ferret out the meaning of a question beyond the literal words that are used. This is easy for humans. It’s tough for computers.

How Google Understands Things

Unlike a human, Google largely cannot look past the actual words that are used in a question.

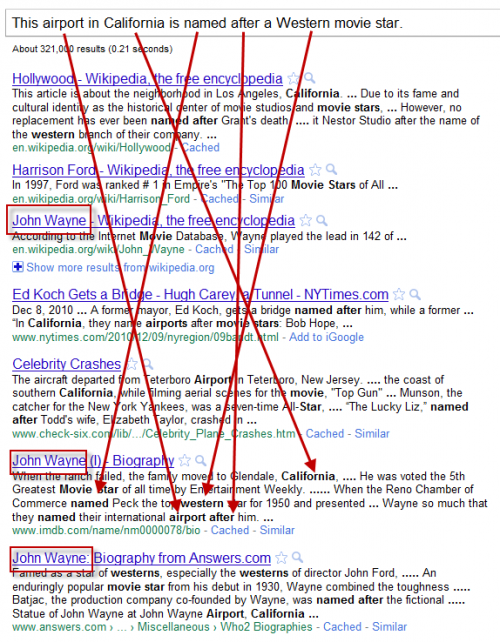

To illustrate this, I’ve given Google a different airport question below (there’s no sense using yesterday’s question, because at this point, all of Google’s results are now filled with references to the yesterday’s show). I’ve asked Google:

This airport in California is named after a Western movie star.

The answer I’m thinking of is my local airport in Orange County, California: John Wayne Airport. How’s Google react to that question?

For the most part, Google doesn’t try to figure out what words mean. Instead, it’s just looking through the billions of pages that it has collected from across the web. Then it pulls out the pages that have all the words you searched for, as some of the arrows above show.

I’ve greatly simplified Google’s search process. Actually, Google does understand what individual words mean, to some degree. Search for “run,” and it will find pages that say “running,” for example. It has smarts to know that “apple” in some cases refers to the computer company while in other cases refers to the fruit.

But for the most part, Google still isn’t trying to “understand” what was entered. It’s really looking for matching words.

How Watson Understand Things

Watson is doing more than match words. Watson is trying to understand the meaning behind sentences. One of the Watson background videos gives a good example of this.

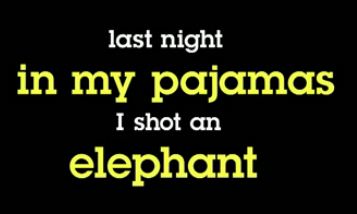

“Last night I shot an elephant in my pajamas” is a statement given:

From that, a question: “Who’s in the pajamas?”

Then there are examples of ways the statement could be interpreted to answer the question. Was it the elephant in the pajamas?

Or the person giving the statement?

Watson tries to understand how to correctly “read” the questions it receives, as well how to read the information it knows, in order to find answers. The articles below provide more information about this process:

- Will Watson Win on Jeopardy!?, NOVA

- A Computer Called Watson, IBM

- How IBM’s Watson hammered its Jeopardy foes, InfoWorld

- The Machine Age, New York Post (written by Google’s director of research, Peter Norvig)

How Do They “Know” Anything?

With the question received and understood by both Google and Watson in their own unique ways, next it’s time to see if they know any answers. But since neither Watson or Google went to school, how do they know anything at all?

Google’s answers come from having gathered billions of web pages and other material from across the internet, a collection in the search engine world that’s called an “index.”

Watson is searching through its own collection of documents. Rather than billions of pages covering all types of subjects, Watson combs through millions of pages from specialized and trusted publications. From the IBM web site:

It has been loaded with millions of documents, including dictionaries, encyclopedias, taxonomies, religious texts, novels, plays and other reference material that it can use to build its knowledge.

How Do They Pick The Right Answer?

As explained earlier, Google looks through its index of documents to find those with words that match what was initially asked, for the most part. After that, Google tries to decide which are the best pages to your answer using a variety of signals, a recipe for ranking pages, something called its search “algorithm.”

More than anything else, Google tries to put pages that seem to have the best “reputation” as measured by links at the top of its list. Ultimately, however, it’s up to a human to make the final choice from the results that Google presents.

Watson also has a search algorithm. In fact, rather than one single algorithm made up of various ingredients, Watson has more than 100 different algorithms that it runs. Again, from the IBM site:

When a question is put to Watson, more than 100 algorithms analyze the question in different ways, and find many different plausible answers–all at the same time. Yet another set of algorithms ranks the answers and gives them a score. For each possible answer, Watson finds evidence that may support or refute that answer. So for each of hundreds of possible answers it finds hundreds of bits of evidence and then with hundreds of algorithms scores the degree to which the evidence supports the answer. The answer with the best evidence assessment will earn the most confidence.

So Watson, while it is presented as a single person, really has like 100 different people inside of it all trying to come up with the right answer. Unlike Google, it can’t rely on looking at how people link to decide what are the best answers. Instead, it’s relying much more on trying to actually understand the knowledge it has “read.”

Is Watson Better Than Google?

Make no mistake — I’ve found Watson amazing. It is amazing, and all the people involved have created something incredible. But the IBM promotions running alongside the show have put me off a bit. That’s probably because I’m so familiar with web search and understand deeply how amazing it is. Despite this, few people appreciate the revolutionary technology happening underneath the hoods of Google or other search engines like Microsoft’s Bing.

Take what one IBM spokesperson said recently:

I’m really focused on the many real-life situations for this ability to be able to dive into unstructured data and make sense of it. The kind of search we do on a search engine today is much more keyword oriented and this is way beyond that … If we can search with intelligence, it could open up all sorts of new fields and possibilities.”

In other words, search engines like Google or Bing are way behind Watson, which is backed by a buzzword filled promotional site that talks about Watson answering questions in less than three seconds.

Three seconds is actually a very long time. Google and Bing answer questions in a few tenths of a second. They answer these questions, largely accurately, by looking through billions of documents, not millions.

In addition, Google and Bing answer thousands of questions being asked every second. Not one single question being asked by one person, as happens with Jeopardy. And they do this without repeatedly crashing, as Watson did.

How Google Trumps Watson

Imagine a Jeopardy round where Trebek tossed out 1,000 questions all at the same time to two human contestants and Google. Google would get the majority of them right — and within a single second. The human challengers would be trounced. Even Watson couldn’t keep up.

That’s the type of power that happens with web search. We’ve just had it so long — and it developed so quickly as an actual consumer product — that we don’t hold it in awe. We should.

Natural Language Reality Check

The reality is that the technology that Watson demonstrates, while amazing in a game show, is overkill for what most people need. Those behind “natural language” search technologies have long trotted out sentences like the “Who’s in the pajamas” example above to demonstrate how “smart” their search tools are. And yet, most searches people do on search engines are only two or three words long.

Among the “hot” searches right now on Google, as I write this article, are “online stopwatch” and “borders bankruptcy.” You don’t need a lot of natural language processing to understand these queries.

In the consumer search world, we’ve had promises of a natural language revolution many times before. In 2008, Powerset promised the type of understanding that Watson is doing now. Microsoft eventually bought it. That natural language processing is now a tiny element within Bing — most likely not used more because it added little to Bing but took huge amounts of processing power to implement.

Wolfram Alpha offered something similar in 2009. The service continues to operate, but it has gained no huge audience nor sparked a major revolution among the established search players.

IBM’s Past (& Failed) Search Plays

Meanwhile, for all IBM suggests about how Watson will transform the world — we’ve been here before with IBM. The company’s Clever project leveraged links to improve search before Google arrived. IBM failed to capitalize on that technology.

In 2003 and 2004, IBM’s WebFountain was positioned in ways that eerily sound like what Watson’s now supposed to do. From a News.com article about the project at the time:

By contrast, IBM’s WebFountain wants to help find meaning in the glut of online data. It’s based on text mining, or what’s called natural language processing (NLP). While it indexes Web pages, it tags all the words on a page, examines their inherent structure, and analyzes their relationship to one another. The process is much like diagramming a sentence in fifth grade, but on a massive scale. Text mining extracts blocks of data, nouns-verb-nouns, and analyzes them to show causal relationships.

WebFountain no longer exists. The former site doesn’t even show any trace of the former project (instead, see this article from John Battelle at the time). The same is true for IBM’s “Marvel” multimedia search engine project from 2004.

But It’s Sure Fun!

Whether Watson pans out as something beyond an fantastic publicity stunt for IBM remains to be seen. Many experts do agree that natural language processing offers some real advantages in some search situations. Especially for corporate search needs, maybe the amazing picture that IBM paints will come true.

In the meantime, we can all enjoy the show. And who knows — maybe in a few years, Google will decide it should do its own version of a Jeopardy challenge. Our previous article below covers research showing that Google’s already pretty good:

Contributing authors are invited to create content for Search Engine Land and are chosen for their expertise and contribution to the search community. Our contributors work under the oversight of the editorial staff and contributions are checked for quality and relevance to our readers. The opinions they express are their own.

Related stories

New on Search Engine Land