Right To Be Forgotten: Do Users Even Care?

In the last few weeks, two monumental events related to Internet privacy caused the biggest uproar in discussions about personal privacy since Edward Snowden’s revelations about the NSA. In May, the European Court of Justice ruled that Google must respect the “right to be forgotten” and at the request of private individuals remove “irrelevant” and […]

In the last few weeks, two monumental events related to Internet privacy caused the biggest uproar in discussions about personal privacy since Edward Snowden’s revelations about the NSA.

In May, the European Court of Justice ruled that Google must respect the “right to be forgotten” and at the request of private individuals remove “irrelevant” and “outdated” information. To comply with the ECJ’s ruling, Google set up a form online for individuals to have their information removed from the web, and they have been deluged with requests.

Last month, during its Worldwide Developer Conference, Apple announced that the DuckDuckGo search engine would be added to Safari as a search engine option. DuckDuckGo is focused on user privacy and even calls itself “the search engine that doesn’t track you.” Having it listed as a search engine option alongside Google, Bing and Yahoo will potentially give it a massive boost in popularity and allow even more people to start using it as their default search engine.

These two events got us at SurveyMonkey thinking about how much people really care about privacy. Do things like “the right to be forgotten” and non-tracking search engines even matter? Using SurveyMonkey Audience — our tool with on-demand access to millions of survey takers — we were able to gather a sense of what the American public thinks about privacy.

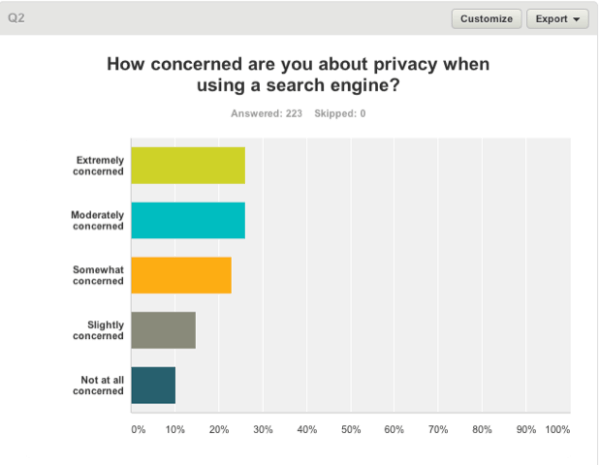

Of the people we polled, 26% indicated that they are “extremely concerned” about privacy when using a search engine, with nearly 90% expressing some level of concern.

Yet when we asked which search engines they ever use, 92% use Google, 22% use Bing and 20% use Yahoo. Only 3% of people answered that they ever use DuckDuckGo — fewer than use AOL.

Despite the limited usage of DuckDuckGo, the data nonetheless suggest that the public is eager for its particular services. With so many people concerned about search engine privacy, they might be pleased to learn about DuckDuckGo’s non-tracking features.

To get a sense of why people might be concerned about privacy when using a search engine, we asked respondents if they have ever conducted a search that they might be embarrassed for someone else to see. The results on this question were an even 50-50 split.

We also asked users to share the general topics of these embarrassing searches. Not surprisingly, medical searches were the most common embarrassing type of search (57%), with pornography coming in at second at 45%.

Rounding out the list was “seeking information on old relationships” at 36% and pirating media at 15%. And finally, 10% of users revealed that they were embarrassed by searches that were unmentioned in the categories we provided. One brave respondent admitted his or her embarrassment about “murder research for novel writing.”

When asked about the types of precautions taken to protect their online privacy, 58% of respondents reported that they delete their history and 53% delete their cookies. Curiously, only 27% use incognito or privacy mode in their browser, suggesting a lack of awareness about this feature.

Respondents reported being comfortable with websites having access to the keywords used to arrive on those sites. Only 16% claimed to be uncomfortable with this sharing of information. Google removing the query information from referral logs (not provided) to “protect users” might have been a protection that users don’t care that much about.

On the other hand, the timing of Google’s move towards 100% secure search fell very close to the leak about NSA snooping — and perhaps this was no coincidence. Hiding keywords to prevent government snooping seems like something users might actually appreciate.

Respondents expressed some concern about government agencies accessing their search history. (There was definitely a lot more concern about the government seeing this data than other websites.) Eighteen percent were “extremely concerned,” 26% were “not concerned at all,” and the rest fell somewhere in the middle.

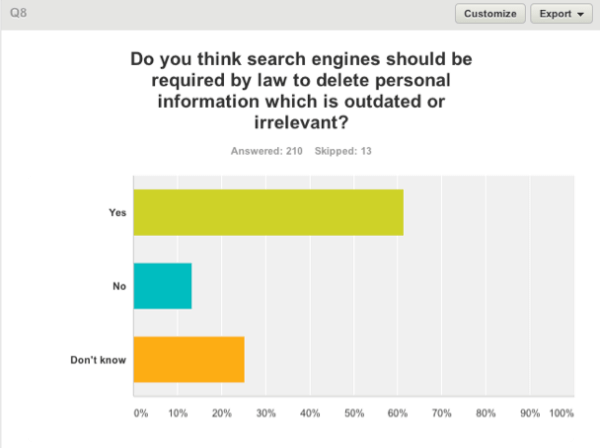

On the topic of government — the primary area of interest behind this survey — a significant majority of respondents (62%) would like the government to force search engines to remove “outdated and irrelevant” information. Thirteen percent were against a legal requirement, while 25% were unsure how they felt on the topic.

In line with these answers, only 5% of respondents would not be influenced in their search engine choices by this feature. Nonetheless, 64% would take advantage of this feature if it were offered. This overwhelming show of support for the removal of one’s name from a search results could be deeply problematic for Google and could potentially change the web as we know it.

What would you do? If given the option, would you want to remove yourself from completely and irrevocably from the web?

Contributing authors are invited to create content for Search Engine Land and are chosen for their expertise and contribution to the search community. Our contributors work under the oversight of the editorial staff and contributions are checked for quality and relevance to our readers. The opinions they express are their own.

Related stories

New on Search Engine Land