The Growth Of Framebars & Kevin Rose On The DiggBar

The DiggBar has been out for about a week now. Since then, there continues to be concerns over twin issues of whether it robs sites of link love and frames their contents in a way that’s unfair to publishers. I had a good conversation with Digg cofounder Kevin Rose today about these issues and how […]

The DiggBar has been out for about a week now. Since then, there continues to be concerns over twin issues of whether it robs sites of link love and frames their contents in a way that’s unfair to publishers. I had a good conversation with Digg cofounder Kevin Rose today about these issues and how Digg is actively looking at ways to solve worries over the tool.

For those unfamiliar with the DiggBar, it allows people to create a short URL that’s useful in services like Twitter. Anyone clicking on a shortened URL made through Digg gets to a page with a DiggBar at the top. For example, here’s how it looks for a post I recently did on my personal blog about newspapers and concerns over Google:

The red arrow points at one feature, how the DiggBar allows anyone to vote on the page they’re viewing. There are other handy features, such as the ability to see any comments people have made at Digg about the page:

There’s no doubt that if you use Digg a lot, you’ll probably love the DiggBar. But the bar does two things that aren’t making some people (including me) very happy. It doesn’t pass along link credit, and it frames web content.

Link Credit Issues

Last week, my URL Shorteners: Which Shortening Service Should You Use? article went into depth about how various URL shorteners work. A key issue is whether these shorteners tells search engines to credit the destination URLs they point at. Those issues what’s called a “301 redirect” do this correctly (my What Is Google PageRank? A Guide For Searchers & Webmasters article covers more about link credit issues and why it is important to search rankings).

The DiggBar does not do a 301 redirect (nor can it, as this would prevent the DiggBar from showing at all). If you shorten a page using DiggBar service, then Twitter the short URL you receive, any links that Google or other search engines find via that short URL will send credit to Digg, not to the destination page you shortened.

A sidenote here. Twitter automatically puts a “nofollow attribute” on any links that people tweet. That’s a method to tell search engines that the links shouldn’t be counted as “votes” as part of their ranking processes. However, tweets often appear off the Twitter.com domain. In some of these places, the nofollow attribute (or tag) doesn’t get used. So tweeted links can get counted by search engines, and it remains important that URL shorteners pass along credit to the destination pages.

Digg had a blog post out yesterday explaining that they had done some things they believed would stem concerns about link credit not flowing properly. SEO expert Greg Boser dissected that post, finding it didn’t hold up. I also looked at it today and found problems:

1) Using the noindex tag prevents the pages that Digg makes with shortened URLs from being spidered by Google and other search engines, but that does not solve the issue of them still accumulating all the link credit rather than this going to the destination URL. Also, so far despite using noindex, some of these pages are getting listed in Google. Here’s another example of this. (Looking at the source code, that page lacked a noindex tag an a canonical tag. It seems like originally, the DiggBar didn’t add these tags. Now that they are present, it will take search engines a few days to weeks to catch-up).

2) Using the canonical tag as a form of redirection doesn’t work, because that tag is still treated as a “hint” by search engines rather than an must obey instruction. It also doesn’t work across different domains (IE, Digg.com can’t point at content off Digg.com’s own domain and use the tag to tell the search engines anything).3) The “source URL” solution Digg discusses doesn’t solve anything. What this means is that if you’re on the Digg home page, stories are listed there from across the web. For example, here’s a popular one right now from the Daily Telegraph:

Digg uses a short URL to point you at that story, which in turn brings the DiggBar up on the top of the page. However, if you can’t run JavaScript (as search engines operate), then you get the long “source URL” like this:

Digg’s thought was that by showing the long “source” URL to search engines, then the long URL ultimately will get all the link credit. However, there are plenty of places where the short URL will be found across the web by search engines because it is listed with regular HTML, rather than through JavaScript.

Framing Issues

Back in the late 1990s, framing was a big issue. For those unfamiliar, frames allow a web site to pull in content from other web sites into their own pages. It was much loathed for a variety of reasons. It often led to bad user experience. It caused serious issues for search engines, making it difficult for them to spider content properly. Some felt it was a copyright violation — that the site doing the framing was effectively copying their material without permission.

Framing largely disappeared for all of these issues. But now it’s coming back, and Digg’s use with the DiggBar may have been the tipping point.

Last October, StumbleUpon added framing of sites, so that anyone starting a browsing experience from StumbleUpon’s home page gets a framebar like this, as the red arrow points at:

Back in December, Facebook added its own framing of content through a framebar that appears when you click on posted links from within the service. Again, the red arrow points to an example that you can see for yourself here:

Ask.com started framing search results in February. The red arrow below points to the framebar, which appears when you click from Ask search results to a web page that’s listed, like this:

Ask used to do this when it first started out back in the 90s, then dropped framing apparently because so many sites moved away from that model. Now with harder economic times, it apparently finds value in trying to take over the top part of your browser window.

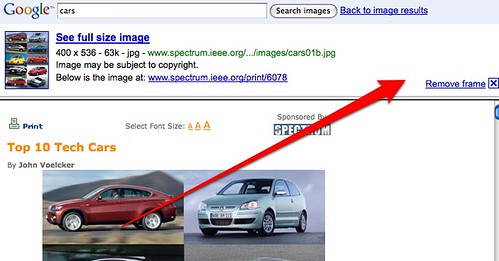

Of course, Google also frames web sites with its Google Image Search service. I believe it has operated this way years and years ago from when image search first started:

There was actually a lawsuit over this, which Google won. Despite that, this might be a good time for Google to reconsider the framing it does.

Also, if Google were ever to frame web sites when you click to them from search results in the way Ask does, the web would almost certain erupt in anger. I don’t think this will happen, of course — but if it’s not something we’d allow Google to do, it’s not something we should be allowing any sites to do.

Framebars Versus Toolbars

Clearly Digg didn’t start the new wave of framing, but it certainly has taken much more heat than Facebook or StumbleUpon over it. I think it’s the combination of URL shortening with framing that’s tipped people over the edge. That mixed framing with the popularity Twitter, where most people these days seem to be using URL shorteners. I think it creates worry that there will be no stopping framing or framebars now.

I feel for services like Digg and Facebook and StumbleUpon. The framebars they’ve created are useful and certainly easier than having users install toolbars for their browsers. But they remain frames, and they bring with them all the negatives about frames that we had in the past.

I’d hope that perhaps there’s an industry move to develop some standards around framebars. For example, if they’re going to be used, perhaps they are less intrusive to a publisher if shown at the bottom of a browser window, rather than at the top. Perhaps there’s also a way to ensure that the URL showing in the browser window remains that of the “source” site with the framebar also displayed (it’s been a long time since I played with frames, so I’m not sure this can be done).

Other ideas might include developing a standard script that publishers can use if they want to break frame code but also inform visitors from a particular site (such as Digg or Facebook) that they can get similar functionality using software toolbars. Perhaps pop-up toolbars in a separate window could work, though there are issues with pop-up blockers.

I don’t know the right answer. Personally, I think the easiest thing would be for everyone to just say no to frames. If you want your dedicated users to have toolbar-like functionality, then have them install an actual toolbar, not a framebar.

Kevin Rose On DiggBar

How’s Digg viewing the uproar? “It’s been a crazy learning experience for us,” Rose said. “We want to follow best practices.”

Rose explained that initially, Digg wanted simply to do a toolbar to help their most active users more easily Digg content or comment on it.

“We wondered what can we create that allows people to go visit that site with a single click and still get a Digg experience. That was kind of the idea behind creating the bar in the first place,” he said.

More as an afterthought, when seeing how popular it was to shorten URLs on Twitter, Digg added on a shortening aspect to the DiggBar.

“The goal in creating this wasn’t, ‘Let’s be the universal URL shortener.’ It was ‘Let’s make a tool that can enhance the experience for Digg users’.”

Rose said someone at Digg did speak with a software engineer at Google, as mentioned in their blog post, about the best way to pass along credit to Google — but he didn’t know who that was. Fair to say, they’ll get the straight scoop shortly, as Rose is now set to speak to Matt Cutts, who heads Google’s spam fighting efforts and who also closely watches over webmaster issues.

As for the DiggBar’s future itself, Rose said the company is taking in all the feedback to determine what’s the next best step.

“I want to make it known by all means that we’re sitting down and thinking about this stuff and trying to come up with solutions that work for anyone,” he said.

What’s A Webmaster To Do?

While Digg reexamines the DiggBar, there are webmasters who will remain concerned. My original article on URL shorteners has code you can use to block framebars. Wikipedia has a page about this, too, and you can see John Gruber’s code here. By the way, we actually had that code on our site before the DiggBar came out, just as a general best practice of breaking frames.

Of course, if you like the idea that people can more easily Digg (or Stumble or Facebook) your content, then you might not have an issue with using the frames.

I’d still recommend that if you’re wanting to shorten URLs for your own sites, use a service that’s primarily built for that and which does 301 redirect.

Contributing authors are invited to create content for Search Engine Land and are chosen for their expertise and contribution to the search community. Our contributors work under the oversight of the editorial staff and contributions are checked for quality and relevance to our readers. The opinions they express are their own.

Related stories