Court Finds Google’s Book Scanning Is Fair Use: Highlights From The Ruling

Nearly ten years after it began and eight years after Google was sued over it, Google’s program that scans books in order to make them searchable has been found legal. A judge found fair use, especially in that “Google Books does not supersede or supplant books because it is not a tool to be used to […]

Nearly ten years after it began and eight years after Google was sued over it, Google’s program that scans books in order to make them searchable has been found legal. A judge found fair use, especially in that “Google Books does not supersede or supplant books because it is not a tool to be used to read books.”

The ruling by Judge Denny Chin found that the Authors Guild’s claims that Google was massively infringing the copyright of books didn’t hold up. Below, some of the key highlights from his ruling.

The Background & Permission Needed To Scan?

Most of the ruling covers the background of how Google Books works and the allegations in the case. It starts covering the two programs Google uses to gather books for Google Books:

Partner Program: First is the the Partner Program, which started in December 2003. The ruling says 2004, probably a reference to when the program came out of beta and opened more widely to publishers. Books scanned through the partner program haven’t really been an issue because publishers or authors themselves have actively given permission for their works to be used in Google Books. From the ruling, about 2.5 million books have been scanned this way.

Library Program: With the Library Program, which began in December 2004, Google began scanning books provided by various major libraries. To date, the ruling says Google has scanned over 20 million books, in this method. Unlike the partner program, Google didn’t have express permission to scan these books. From the ruling:

Google did not seek or obtain permission from the copyright holders to digitally copy or display verbatim expressions from in-copyright books.

That’s the core of this entire case. While Google didn’t get permission to scan these books, did it actually need that permission — or was its scanning covered under fair use laws?

Display Of Snippets, Not “Full View” Books

Despite what you may have heard, Google Books does not — and never did, to my knowledge — display the full text of any book that it scanned without having express permission to do so from a publisher, author or other rights-holder. Google also has “full view” copies of books for those that are clearly out of copyright.

For other books, those in copyright and obtained through the Library Program, Google will show “snippets,” short passages that match the words someone searched for within Google Books. Here’s how it looks when I did a search for words I knew would bring up a passage from “Ball Four,” one of the three books cited in the copyright infringement case against Google:

Clicking on the Ball Four link brings me to a page at Google Books showing the actual scan of that passage:

The entire text of the book isn’t shown. In fact, the publishers can even block snippets from being shown by asking that Google remove their books entirely from Google Books.

Reading Snippets Is Not Reading A Book

Could someone use the ability to view many snippets as a way of reading an entire book, or reading just the important stuff they want to avoid buying a book — especially in cases of “short text” works like recipe books? The judge didn’t buy this argument, spending time discussing Google’s security measures designed to prevent this:

Each search generates three snippets, but by performing multiple searches using different search terms, a single user may view far more than three snippets, as different searches can return different snippets. For example, by making a series of consecutive, slightly different searches of the book Ball Four, a single user can view many different snippets from the book.

Google takes security measures to prevent users from viewing a complete copy of a snippet-view book. For example, a user cannot cause the system to return different sets of snippets for the same search query; the position of each snippet is fixed within the page and does not “slide” around the search term; only the first responsive snippet available on any given page will be returned in response to a query; one of the snippets on each page is “black-listed,” meaning it will not be shown; and at least one out of ten entire pages in each book is black-listed.

An “attacker” who tries to obtain an entire book by using a physical copy of the book to string together words appearing in successive passages would be able to obtain at best a patchwork of snippets that would be missing at least one snippet from every page and 10% of all pages. In addition, works with text organized in short “chunks,” such as dictionaries, cookbooks, and books of haiku, are excluded from snippet view.

Google Books As A Public Benefit

Next, the judge went on to highlight five main benefits of Google Books:

- Easy way to find books & research information

- Helps with data mining about language trends and changes

- Expands access to books

- Preserves old and out-of-print books

- Helps authors and publishers gain audience and income

A few passages about some of these benefits. Here’s one about the research importance:

Google Books has become an essential research tool, as it helps librarians identify and find research sources, it makes the process of interlibrary lending more efficient, and it facilitates finding and checking citations. Google Books has become such an important tool for researchers and librarians that it has been integrated into the educational system — it is taught as part of the information literacy curriculum to students at all levels.

Here’s one on book preservation:

Google Books helps to preserve books and give them new life. Older books, many of which are out-of-print books that are falling apart buried in library stacks, are being scanned and saved. These books will now be available, at least for search, and potential readers will be alerted to their existence.

Google Books Brings New Audiences & Income To Rights-Holders

The benefits section wraps up with this key passage:

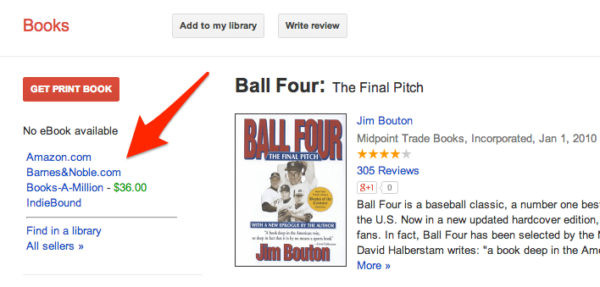

By helping readers and researchers identify books, Google Books benefits authors and publishers. When a user clicks on a search result and is directed to an “About the Book” page, the page will offer links to sellers of the book and/or libraries listing the book as part of their collections. The About the Book page for Ball Four, for example, provides links to Amazon.com, Barnes&Noble.com, Books-A-Million, and IndieBound. A user could simply click on any of these links to be directed to a website where she could purchase the book. Hence, Google Books will generate new audiences and create new sources of income.

Here’s how those links look, by the way:

Yes, Scanning Is Fair Use

After some further discussion of the history of the case, which was restarted after a proposed settlement fell-through in 2011, the judge explains that that when it comes to whether the book scanning is fair use, he finds that it is:

The sole issue now before the Court is whether Google’s use of the copyrighted works is “fair use” under the copyright laws. For the reasons set forth below, I conclude that it is.

Google Books Is Transformative

One of four factors the judge says in determining if something is fair use is whether copyrighted material has been transformed into something unique, in a way that adds value to the original without replacing it. On this, Judge Chin is convinced. He notes that Google Books uses the book content to make a book discovery and research tool:

Google’s use of the copyrighted works is highly transformative. Google Books digitizes books and transforms expressive text into a comprehensive word index that helps readers, scholars, researchers, and others find books….

Words in books are being used in a way they have not been used before. Google Books has created something new in the use of book text — the frequency of words and trends in their usage provide substantive information.

The section on transformation goes on to say that just because Google is a for-profit service, that doesn’t outweigh the ability for fair use to apply. Transformation is also seen as a factor “strongly” in favor of a fair use finding.

Google Books Is Not A Book-Reading Service

One passage in the transformation section seemed so key to me that I’m bolding it below:

Google Books does not supersede or supplant books because it is not a tool to be used to read books. Instead, it “adds value to the original” and allows for “the creation of new information, new aesthetics, new insights and understandings.” Hence, the use is transformative.

I’ve written about Google’s book scanning efforts, and the cases against it, from the very start. Over the years, it is extremely common to find those who oppose it to suggest things that are simply not true, chiefly that Google makes copies of books and puts them online for anyone to read.

Except where it has clear permission, Google doesn’t do this. And the judge seems to fully understand that copying books so that people can research what’s within a broad collection is not the same as somehow publishing a digital library that anyone can read.

Amount Used “Slightly Against” Google

Discussion goes on to the second factor, the nature of the works involved — fiction, non-fiction, out-of-print, and the judge says briefly that since the majority are non-fiction, that weighs in Google’s favor — and that the parties in the case further agree that this point “plays little role” in determining fair use, regardless.

Rather, the real focus is on the “amount and substantiality of the portion used” from the copyrighted works. Here, it might be seen as a slam-dunk that Google is copying entire books, so therefore, it must be guilty. But the court notes such copying may be allowed, citing some other cases and noting that the copying is “critical” for Google Books to work:

Google scans the full text of books — the entire books — and it copies verbatim expression. On the other hand, courts have held that copying the entirety of a work may still be fair use. See, e.g., Sony Corp. of Am. v. Universal City Studios, Inc., 464 U.S. 417, 449-50 (1984); Bill Graham Archives, 448 F.3d at 613 (“copying the entirety of a work is sometimes necessary to make a fair use of the image”).

Here, as one of the keys to Google Books is its offering of full-text search of books, full-work reproduction is critical to the functioning of Google Books.

The judge also notes that Google limits what can be shown. Overall, Google is found weaker in this area, but not so weak that it trumps over the other tests:

Significantly, Google limits the amount of text it displays in response to a search.

On balance, I conclude that the third factor weighs slightly against a finding of fair use.

Reasonable People Would Conclude Google Books Helps Sales

The final factor of fair use is whether the new use of works will have a negative effect on the originals. In other words, if Google Books has scanned all these books, does that mean no one will buy them? The judge doesn’t believe so:

Plaintiffs argue that Google Books will negatively impact the market for books and that Google’s scans will serve as a “market replacement” for books. It also argues that users could put in multiple searches, varying slightly the search terms, to access an entire book. Neither suggestion makes sense.

He goes on to explain how difficult it would be for someone to use Google Books as a means to actually read a book:

Nor is it likely that someone would take the time and energy to input countless searches to try and get enough snippets to comprise an entire book. Not only is that not possible as certain pages and snippets are blacklisted, the individual would have to have a copy of the book in his possession already to be able to piece the different snippets together in coherent fashion.

In conclusion, he thinks anyone who is “reasonable” would find Google Books actually helps sales:

To the contrary, a reasonable factfinder could only find that Google Books enhances the sales of books to the benefit of copyright holders. An important factor in the success of an individual title is whether it is discovered — whether potential readers learn of its existence. Google Books provides a way for authors’ works to become noticed, much like traditional in-store book displays.

Indeed, both librarians and their patrons use Google Books to identify books to purchase. Many authors have noted that online browsing in general and Google Books in particular helps readers find their work, thus increasing their audiences. Further, Google provides convenient links to booksellers to make it easy for a reader to order a book.

“No Doubt But That Google Books Improves Books Sales”

The judge concludes with strong statement that there’s no doubt that Google Books helps the sales of books, leading him to find on this fourth point in favor of fair use:

In this day and age of on-line shopping, there can be no doubt but that Google Books improves books sales. Hence, I conclude that the fourth factor weighs strongly in favor of a finding of fair use.

The Broader Implication: Search Engines Are Safe, Too

The ruling provides a sum-up of what was previously said but doesn’t really add more other than to grant summary judgement in Google’s favor. The Authors Guild can appeal and has posted to its site that it will.

The ruling also provides, if upheld, an important precedent for Google’s “scanning” of the web. Because that’s what search engines like Google and Bing do, make copies of pages from across the web in a similar manner to how Google copied books.

There have been a few minor cases against web indexing over the years, but no one has seriously challenged a search engine from indexing documents, primarily in my view because it’s easy for rights-holders to opt-out and because they don’t, wanting the traffic.

But should such a case happen in the future, the Google Books ruling will be instrumental in any court fight.

For more about the case, see additional coverage at Techmeme. Jeff John Roberts has a nice write-up at GigaOm with some reaction tweets, and he’s made a copy of the case availble here:

Contributing authors are invited to create content for Search Engine Land and are chosen for their expertise and contribution to the search community. Our contributors work under the oversight of the editorial staff and contributions are checked for quality and relevance to our readers. The opinions they express are their own.

Related stories