Is Google’s AMP carousel working? (Or, SEO insights from Kanye West)

Publishers are asking questions about the effectiveness of Google’s AMP carousel. Columnist Barb Palser analyzed 235 million AMP search impressions to find answers.

They also provide a brand showcase publishers should love.

AMP “Top Stories” scrolling rich card carousel in Google mobile search

But recently, publishers have been scratching their heads over analytics indicating AMP content has a lower click-through rate from rich cards than from general search results. They’re finding this data in Google Search Console (GSC), which now allows publishers to filter AMP performance in search based on appearance as rich cards in a carousel vs. non-rich text links.

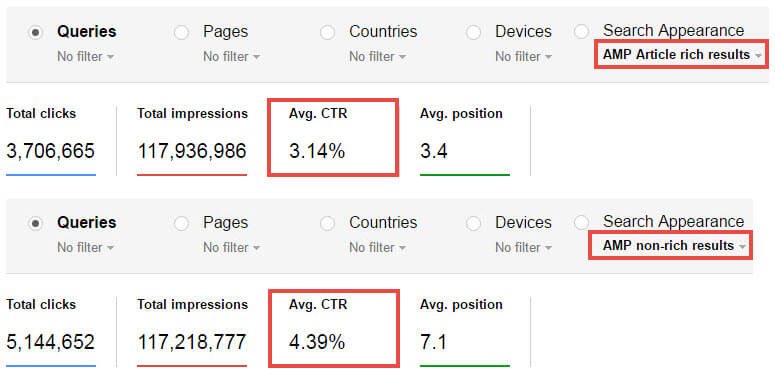

Here’s the GSC dashboard for an aggregated group of news publishers, showing an average CTR of 3.14 percent for AMP rich results vs. 4.39 percent for AMP non-rich results, even though the rich results have a higher average position.

Google Search Console rich vs. non-rich performance for an aggregated group of news publishers with a total of 235 million AMP search impressions and 8.9 million AMP clicks

These numbers are perplexing at first — but, if we dig in, they begin make sense.

Reason #1: Relevance and supply

In a nutshell, the rich card carousel favors broad searches. The carousel is invoked when a query returns at least three AMP results Google deems relevant enough to display together. The broader and more popular the search, the more likely the threshold will be met and the results displayed as a carousel of up to 10 rich cards. However, broad searches often result in lower click-through rates than precise searches.

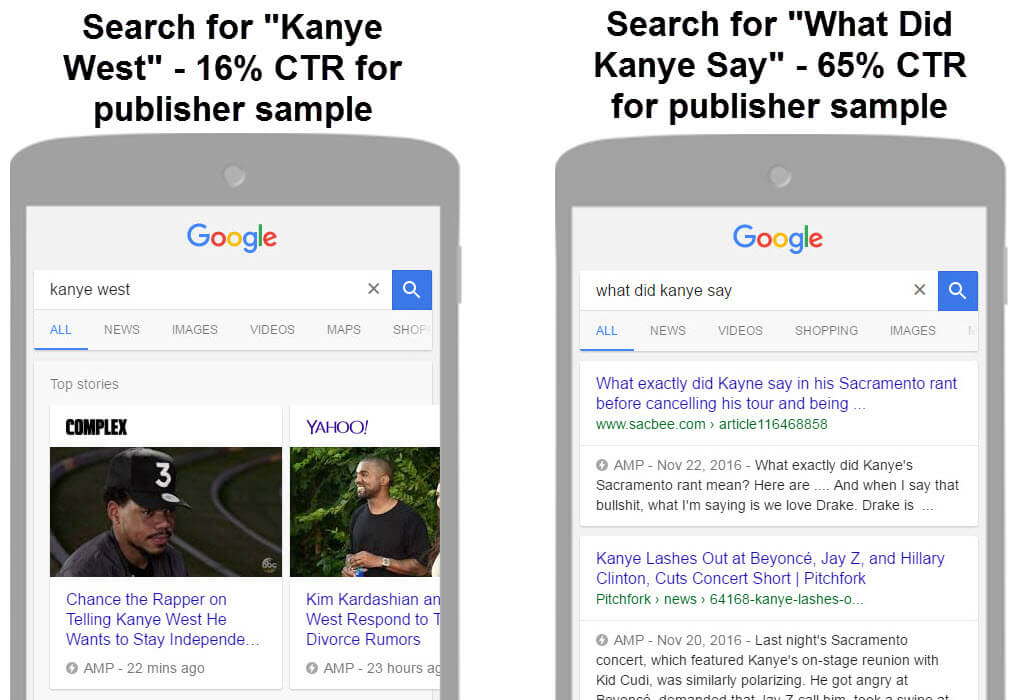

For example, for the aggregated news publishers above (a mix of hyperlocal, local and national brands), “Kanye West” was one of the most successful search terms for the time span analyzed, by volume of resulting AMP impressions and clicks. Because there’s a vast supply of close-match AMP results for the general term “Kanye West,” the results were always displayed as a rich card carousel — with a very good click-through rate of 16 percent.

Measured by engagement, however, the most successful Kanye-related search term was “What Did Kanye Say,” with a phenomenal click-through rate of 65 percent. The precise query was searched less often, producing a lower volume of impressions and clicks — but yielded highly relevant results. Without enough close matches to meet the AMP carousel threshold, Google displayed the results as text links.

Broad and popular search results are likely to be displayed in an AMP carousel, while very granular search results are often displayed as text links.

There are many exceptions to this rule. The universe of AMP content is large and growing every day as more publishers become AMP-enabled, such that many granular searches are now invoking the AMP carousel — especially for news and entertainment topics of broad interest.

But on balance, broad and popular search results seem to be concentrated in the AMP carousel, while the long tail of specific queries are more likely to be returned as text links only, tilting the average CTR toward non-rich results for many publishers.

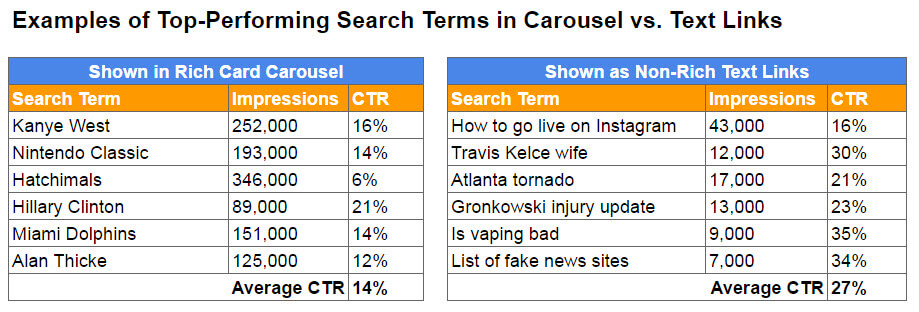

To underscore this point, here are some of the top-performing rich and non-rich queries based on resulting clicks, for the news publishers analyzed:

Top-performing AMP queries by number of resulting clicks, for an aggregated group of news publishers

This is a clear illustration of how mobile search exposure is shifting — and what many non-AMP-enabled publishers are missing by being excluded from the rich card carousel.

Naturally, these metrics will vary by publisher, depending on the publisher’s topical and geographical focus, the pool of competitive AMP content for that focus, overall search optimization and how often users find the publisher’s content from topical searches vs. branded searches.

Reason #2: Carousels are not awesome

As a user interface, scrolling carousels don’t have a great reputation; mostly, they seem to be good at hiding content from users. It appears Google’s AMP carousel is no exception.

On mobile phones, the first two cards in an AMP carousel are visible — or three cards in landscape view. It seems users aren’t scrolling or clicking much beyond that.

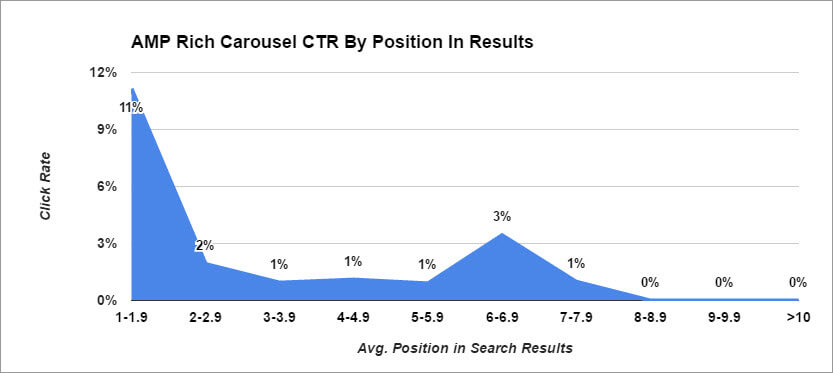

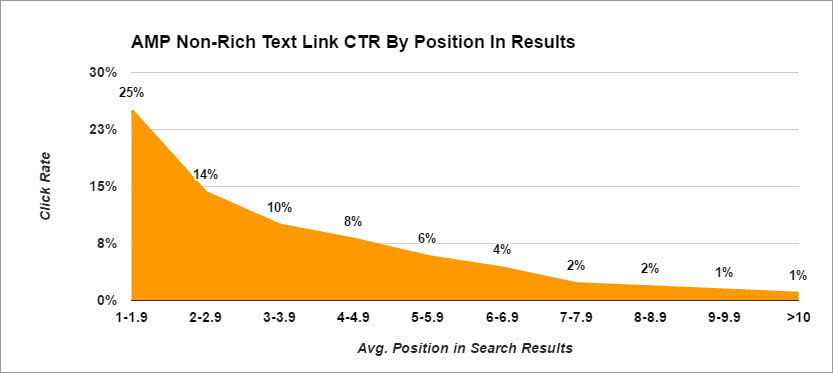

Using the same news publishers and looking at the top 1,000 queries by clicks for both rich and non-rich results, here are the respective click-through rates based on average position in results:

CTR by average position in AMP rich card carousel for the top 1,000 queries across an aggregated group of news publishers. (The 3% “bubble” at 6-6.9 is for an unusually high-performing query.)

CTR by average position in non-rich AMP results for the top 1,000 queries across an aggregated group of news publishers

While both formats show significant declines after the first positions, carousel activity falls off a cliff after positions one and two. Evidently, users are more likely to scroll down to engage with text links than to scroll horizontally to discover additional carousel results.

When publishers rank at the top of results, this isn’t a huge issue — but for publishers who tend to appear deeper in the carousel, it could be a contributing factor to lower rich result CTRs. While this sounds bad, keep in mind that Google often duplicates a publisher’s results in the AMP carousel and in text links. If the publisher’s text link position isn’t affected by carousel appearance, then deep carousel slots are like “bonus” exposure. If deep carousel links displace or replace text links, then concerns would be justified.

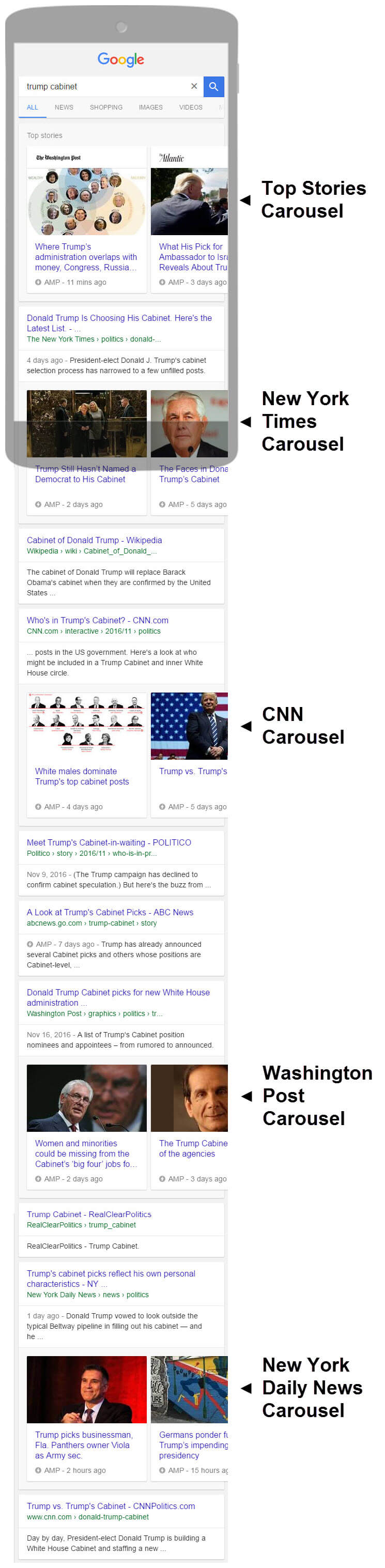

Meanwhile, Google seems to be doubling down on AMP carousels — now displaying publisher-specific carousels when certain publishers have a number of results for a query. It would be interesting to know whether engagement for these single-publisher carousels differs from the multi-source Top Stories carousel. Scrolling notwithstanding, single-publisher carousels are a nice content and brand showcase for publishers who get them.

This search for “trump cabinet” produced four single-publisher AMP carousels in addition to the standard Top Stories carousel:

Google has started surfacing single-publisher AMP carousels in mobile search results.

Conclusion: Blame the carousel, not the cards

All of this analysis suggests AMP carousel CTR is being throttled by (a) the minimum result threshold which prevents rich cards from being displayed for very granular queries; and (b) the shortfalls of carousels in general, which depress CTR for “hidden” content which must be scrolled to view. None of this says anything about the effectiveness of rich cards themselves.

Google could probably boost AMP rich card CTR immediately by reducing or eliminating the threshold for showing results as rich cards, and by displaying them as tiles instead of a scrollable carousel. (Although this might lead to trimming the maximum number of cards in a collection from 10 to something like three or four, in turn reducing rich card impression and click volume.)

The AMP format is a work in progress, as is Google’s careful approach to surfacing AMP in search. Given Google’s focus on performance measurement and fundamental commitment to AMP, we should expect continued optimizations. We might see refinements to GSC reporting as well.

Meanwhile, publishers shouldn’t interpret the click-through rates in their GSC dashboards as an indictment of AMP, or of rich cards for that matter. For a publisher to opt out of AMP based on comparatively lower CTR in the AMP carousel makes no sense at all; that exposure won’t shift back to standard text links — it’ll just go to another AMP-enabled publisher.

Contributing authors are invited to create content for Search Engine Land and are chosen for their expertise and contribution to the search community. Our contributors work under the oversight of the editorial staff and contributions are checked for quality and relevance to our readers. The opinions they express are their own.

Related stories