Why Google’s Reported CPC Declines Can’t Tell The Story Of “A Mobile Advertising Problem”

It’s still happening. Google reported on Thursday that the average cost-per-click (CPC) was down again in Q2 from the prior year, marking the eleventh consecutive quarter in which the average CPC fell year-over-year. Some analysts and news outlets have been pointing to this as evidence of Google’s “mobile problem” — the problem Enhanced Campaigns was […]

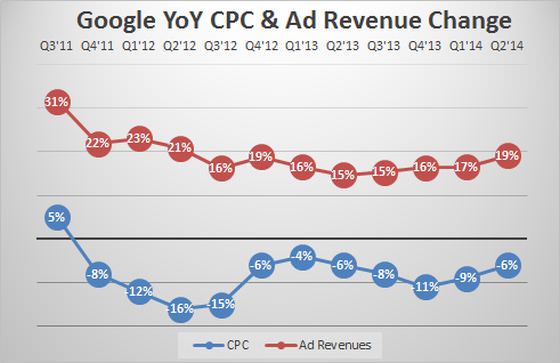

It’s still happening. Google reported on Thursday that the average cost-per-click (CPC) was down again in Q2 from the prior year, marking the eleventh consecutive quarter in which the average CPC fell year-over-year. Some analysts and news outlets have been pointing to this as evidence of Google’s “mobile problem” — the problem Enhanced Campaigns was meant to fix when introduced last year. The fear is that Google can’t figure out a way to monetize mobile ad clicks as the time consumers spend on their phones climbs.

Falling CPCs are interpreted as the canary in the coal mine, signaling that Google’s going to be left behind in the mobile economy and trampled by the likes of Facebook. But is average CPC really any indicator of Google’s market health? Do CPCs matter if click volume is rising (it is) and revenue is growing (it is)?

Truth is, average CPC stats don’t really tell us much at all about what’s happening in Google’s mobile business.

A Brief History

First, let’s look back at what happened when Google introduced Enhanced Campaigns. Google’s public argument for Enhanced Campaigns was to make cross-device paid search campaigns easier for advertisers to manage and ads could be tailored to user context and device. But the move was largely interpreted as the company’s way to bring smartphone and tablet click costs (which advertisers had been discounting) up in line with desktop clicks. Enhanced Campaigns tie tablet and desktop bids together — it is no longer possible to bid separately for tablet traffic. It also means that campaigns are automatically opted-in to smartphone traffic unless advertisers set what’s called a bid modifier to lower the bid on mobile as a percentage of the desktop/tablet bid — by as much as negative 100 percent.

The thought was that tablet CPCs would be pulled up to desktop levels since the bids are now one-and-the-same, and that loads of advertisers that hadn’t bothered to bid on mobile before would at the very least be bidding more on mobile than they had before. Most AdWords campaigns were converted to Enhanced by the end of July last year.

So what happened? In the third quarter of 2013, Google reported that the average CPCs fell by 8 percent year-over-year. In the fourth quarter, CPCs were off by 11 percent. Yet, in both quarters revenue continued to climb along with increases in click volume.

Concluding that Google’s falling CPCs indicate that advertisers aren’t buying and bidding more for mobile in many regions and industries is a bit like Steve Martin’s character in “The Jerk” exclaiming “He hates these cans!” when he’s being shot at the gas station. We aren’t working with the right information because the rolled-up average click costs give us almost no insight at all into one particular area of the business.

Averages Can’t Tell The Full Story

There are several other (and more likely) causes for the declining CPCs. First, it’s important to understand that Google’s overall average CPC stat doesn’t just reflect search. It includes clicks related to ads served on Google owned and operated properties including search, YouTube engagement ads like TrueView, and properties like Maps and Finance, along with the Network paid clicks from AdSense for Search, AdSense for Content, and Google’s mobile ad exchange that serves in-app ads, AdMob. We don’t know the click share each of these click sources has, so knowing that CPCs increased or decreased on Google Sites (-7 percent) or Google Network (-13 percent) doesn’t tell us much.

(And if you’re wondering how the total percent CPC decline could be 6 percent if Google Sites CPC fell 7 percent and Google Network CPC was off by 13 percent, it’s apparently an example of Simpson’s Paradox. RKG‘s Director of Research, Mark Ballard, explains that it’s likely a function of a relative shift in volume to Google Sites where CPCs are higher.)

The Role Of Emerging Markets

Google has on several occasions noted the impact of emerging markets on overall average CPCs, and it came up again on this week’s earnings call when an analyst asked about CPC growth. When you have more clicks coming from emerging and lower-priced markets, that’s going to bring the total average CPC down.

Covario‘s Alex Funk, senior director, global paid search strategy, who tracks global search trends from the firm’s clients, told me, “We know most of Google’s growth is coming from outside North America, which means they are adding search volume but at a much cheaper auction than their established business. North America business is very strong and has seen CPC inflation for the desktop search — due to plateauing inventory and higher prices on things like PLAs.”

Globally, Covario reported a small increase to CPCs of 2 percent, but Europe, The Middle East and Africa (EMEA) and the Asia/Pacific (APAC) were actually both down 7 percent year-on-year. Overall mobile spend rose 98 percent among Covario’s client set in Q2.

Funk adds, “Currently, Google handles something like 3 billion search queries a day, and I believe they are certainly monetizing a good majority of them. This number is not slowing down. The incremental queries are coming from cheaper regions and sources, such as Asia, Latin America and mobile devices all over the world. While the revenue per search number may be down slightly from past numbers, the sheer volume of queries Google is monetizing is staggering.”

RKG’s Mark Ballard also sees click volume shifting to international markets as potentially “the single biggest factor in Google reporting CPC declines”. RKG’s clients skew retail with campaigns targeted in the U.S. Ballard explains that, in recent years, RKG’s CPC growth rates have run higher while click growth has run lower than what Google’s earning statements show, “reflecting the fact that our data is primarily from the U.S.” where competition is higher and continues to increase. RKG’s clients saw click share on smartphones surpass that of tablets for the first time this past quarter.

CPCs Can Fall Even As Mobile Click Share Rises

George Michie, RKG Co-founder and Chief Marketing Strategist, explains how, as mobile gains more click share, it’s possible to see declining CPCs overall even if mobile CPCs are in fact increasing. Here’s Michie’s illustration of how this can happen:

Hypothetical example, Year 1:

- Desktop CPC = $1 and comprise 90% of traffic

- Mobile CPC =$0.20 and comprise 10% of traffic

- Average CPC for Google = ($1 * 0.9 + $0.20 *.1) = $ 0.92

Year 2

- Desktop CPC = $1.10 and comprises 70% of traffic

- Mobile CPC = $0.30 and comprises 30% of traffic

- Average CPC for Google = ($1.10 * .7 + $.30 * .3) = $0.86

Channels, Advertiser Base, Ad Types And More Matter, Too

Brad Geddes, Founder of Certified Knowledge, also points out that without the context of where the impression are coming from — whether by ad type, device type, channel, industry or region — looking at averages are pretty useless. “As you mention, these CPCs are not broken down by PLAs versus text ads versus display. As YouTube gets more impressions, and at cheaper CPCs than Google Search, that would drive the averages down. However, if YouTube was static in impressions and the growth of impressions was coming from pure search, then the average CPC would go up. In some areas, like local businesses, they are often still increasing in competition, so their CPCs are climbing faster than very mature industries that are bidding by pure ROAS metrics and CPCs are fairly flat. ”

Geddes adds, “Since Google doesn’t break out mobile by search, apps, and non-app display, there’s no way of knowing if these mobile numbers are good or bad. If you saw mobile CPCs declining for search for local businesses, that would be a good indicator that Google is having mobile problems. If you saw that average CPC was declining because there were more app impressions but search was increasing, then you’d know Google is doing well.

Similar effects can be seen by advertiser make, says Geddes, “If all of Google’s revenue came from direct response retailers, mobile would drop as the conversion rates are lower on mobile devices than on desktops. If Google’s revenue all came from service-based local businesses, then mobile CPCs would climb dramatically as mobile converts much better than desktop clicks. So without the context of their advertising base, average CPCs don’t give you a good picture of how Google is doing in these respects.”

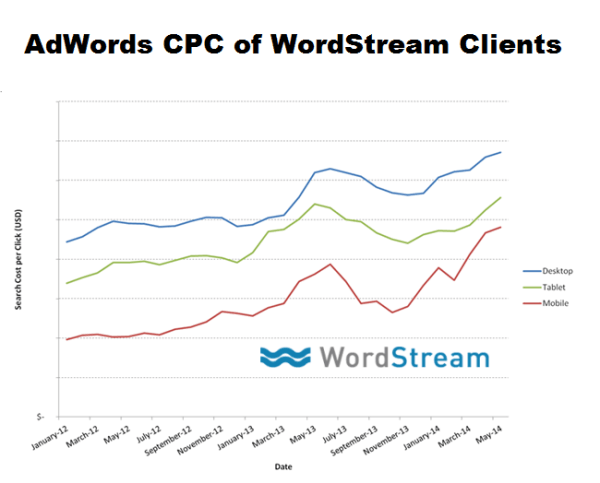

Reports Point To Higher CPCs In Mature Markets

Larry Kim, Founder and Chief Technology Officer at WordStream, says his client data, which is comprised of roughly 2,000 mostly small to mid-sized businesses in English speaking markets, shows trends similar to those seen by RKG and Covario in those regions: CPCs on both desktop and mobile are rising. The combined reporting would indicated that emerging markets are playing a large role in the falling CPCs and that click volumes in those regions are on the rise. (Google’s revenue share from international markets hit an all time high of 58 percent in the second quarter.)

Average CPC Is Not An Indicator Of Market Health

Average CPC Is Not An Indicator Of Market Health

Across the board, the AdWords specialists I corresponded with for this article agree that average CPC is a useless metric in determining whether Google has a “mobile problem”. There are too many variables and data sources packed into that stat to draw any conclusions about the health of one aspect of it.

So why does Wall Street keep coming back to it? Well, for one, it keeps getting reported, and when it goes up (as it did for years until Q3 2011), it is easy to see it as an indicator that advertisers want to buy what’s being sold and are willing to keep paying more for it. Falling CPCs have a tougher time telling a story of rising prices in mature markets but that volume (and business) keeps increasing in lower-priced, emerging markets.

Why doesn’t Google share more detail on how CPCs break down? In a letter to the SEC, Google explained that “disclosing or quantifying the impact of only one factor, such as platform mix, could be misleading and confusing to investors.” Another reason is probably the fact that while questions continue to be raised about mobile, in the end, the stock is going up. Banks and analysts are predicting the stock price will continue to rise.

What’s The Future Of Mobile CPCs?

I asked each of the industry specialists if they thought mobile would catch up to desktop.

Geddes distinguishes between mobile search and mobile app advertising, which perform quite differently. “I don’t think we’ll see mobile CPCs exceed desktop anytime soon. For most B2B companies, mobile isn’t very good so they might do some mobile advertising; but they are much more focused on search. We’ll see local business CPCs exceed desktops, in fact, they might already have; but overall, I think it’s going to be a long time before we see this (if ever). If you were to say mobile search versus desktop; then those two might hit parity in a few years, but as apps don’t do well for many businesses, and those are mostly mobile impressions; the average CPC across all mobile display probably won’t exceed desktops anytime soon.”

Covario’s Alex Funk says they are bullish on mobile spend, “Internally, we forecasted that for 2014 we would have 24 percent of our budgets going to mobile. We’ve already been at 25 percent for the first half of the year. Next year likely will be, by my estimate, at least be a third of the budget, but could be more if the analytics catch up to the increasing demand. Google has a lot in store there with both their homegrown and recently acquired attribution capabilities.”

RKG’s George Michie agrees that Google’s attribution capabilities — estimated cross-device conversions and in-store testing — has helped make the case for raising bids on mobile. Will they surpass desktop bids? Michie says perhaps in some categories such as food, entertainment tickets, travel. However in categories like apparel, consumer electronics, jewelry, Michie says they won’t because it’s “too hard to sniff through a wide selection on a small screen and in-store spillover effects are unlikely to totally offset the conversion differential”.

Larry Kim sees CPC’s continuing to climb, “If I extrapolate the mobile and desktop trends among my clients, I see mobile CPC pulling even with desktop CPC in around 6 quarters time.” Again, he reiterates that his client set doesn’t reflect Google’s entire advertiser base.

In the end, all agree that revenue is the best number to look at when evaluating Google’s advertising strength. Ad revenues hit $14.36 billion in Q2, up 19 percent on the year and 3.6 percent from Q1.

Contributing authors are invited to create content for Search Engine Land and are chosen for their expertise and contribution to the search community. Our contributors work under the oversight of the editorial staff and contributions are checked for quality and relevance to our readers. The opinions they express are their own.

Related stories