Why Patience Is A Virtue With The Long Tail

A recent article by fellow Search Engine Land contributor Matt Van Wagner on long-tail keyword management – as well as some recent experiences with several large-scale advertisers, inspired me to write this article on quantitative long-tail management. Too often, I have seen cases where marketers apply incorrect reactive rules on the long tail and kill it in […]

A recent article by fellow Search Engine Land contributor Matt Van Wagner on long-tail keyword management – as well as some recent experiences with several large-scale advertisers, inspired me to write this article on quantitative long-tail management.

Too often, I have seen cases where marketers apply incorrect reactive rules on the long tail and kill it in effect. This can have a disastrous effect for a large-scale marketer with an ad spend in the hundreds of thousands to millions of dollars a month, where the tail can represent a significant portion of the business.

The Dilemma

Take a look at these two keywords. Which is better?

| Keywords | Clicks | Cost | Orders |

| KW 1 (Head term) | 2000 | $2000 | 40 |

| KW 2 | 30 | $40 | 0 |

Many are tempted to say that keyword 2 is a bad keyword. It has received 30 orders and no conversions. Surely, 30 clicks should be enough to decide if a keyword is good or bad. But is it?

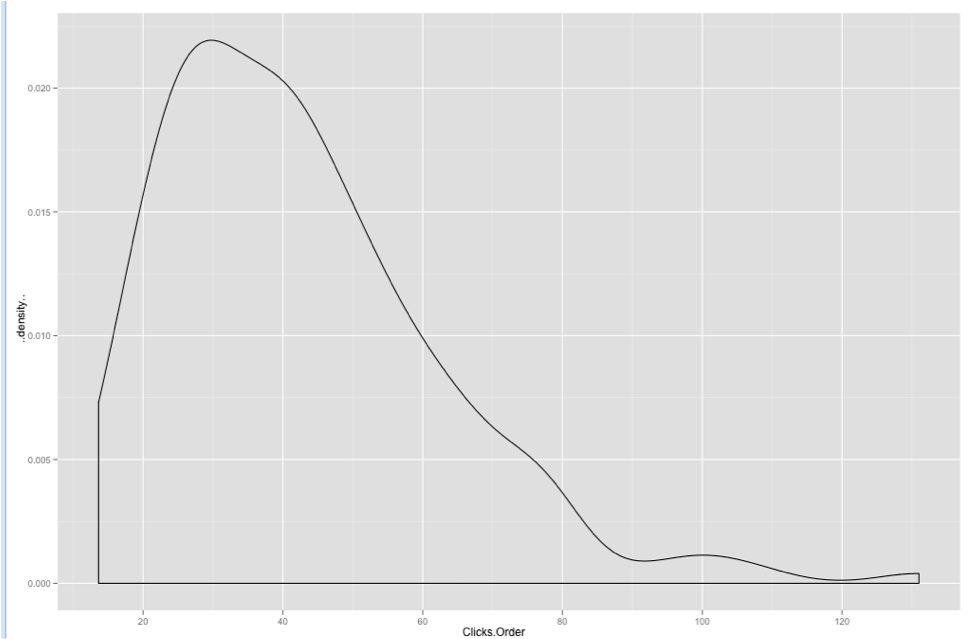

If you look at the head term, the average clicks per order is 2000/40= 50 clicks. Another way to look at the data is to build a histogram of clicks per order for the head terms.

The peak Clicks/Order for the distribution is around 35 (median), and the mean clicks/order is even higher, as there is a significant fat tail to this distribution. Looking at this, one could say that 30 clicks is not sufficient to make a conclusion about the keyword. If I bid this keyword down, then I might miss out on a conversion that I might have otherwise received.

Bucketing: A Better Approach To Look At Data At A High Level

A better approach to measuring the efficacy of the long tail is to group keywords into the number of clicks they received and measure the aggregate. This is shown below:

| Range of Clicks | # KWS | Spend | Clicks | Orders | Clicks/Order |

| 1 to 5 |

2755 |

$7,319 |

15472 |

391 |

39.57 |

| 6 to 10 |

846 |

$5,044 |

13304 |

277 |

47.97 |

| 11 to 50 |

1660 |

$27,263 |

73650 |

1624 |

45.35 |

| 51 to 100 |

274 |

$13,484 |

39132 |

857 |

45.69 |

| 101 to 500 |

291 |

$56,687 |

133800 |

3442 |

38.88 |

| 501 to 1000 |

43 |

$22,670 |

59086 |

1264 |

46.74 |

| 1000+ |

39 |

$57,946 |

233234 |

7637 |

30.54 |

One can clearly see that that head bucket is the best performer, as it has the lowest clicks per order. This is expected here as the head buckets are mostly brand terms.

The 6-10 bucket is the worst performing one that perhaps bears investigation. However, one must note that the key assumption here is that all keywords in a bucket are homogenous in terms of their properties, e.g. consumers will convert and behave with those searches in a similar manner.

Bucketing essentially has an averaging effect and gives us a high level understanding if the performance is strong or poor.

The Danger Of Short Revenue Windows

Too often, I notice advertisers using a short window when determining a keyword’s efficacy. I have seen tail management rules such as “If a keyword has 10 or more clicks in 7 days and no conversions it should be bid down”.

These arbitrary rules can easily kill the long tail, as the parameters (clicks and days) do not account for:

- The average number of clicks you need for a conversion

- The average time taken for a given tail term to get the number of clicks.

In my research, I have found that typically 40-50% of keywords that get clicks in one month do not get clicks in the next month. Moreover, a conversion event might take several months to occur for a tail term.

A rule like the one above will systematically kill tail terms, for at any given point in time a set of tail terms will appear “bad” will be bid down before they can become “good” again.

Five Tips For Effective Long Tail Management

- The best way to manage your long tail is to use statistical algorithms that determine the probability of conversion given the number of clicks a keyword has while using the distribution of clicks per conversion on keywords with enough data (mathematically called the “prior”).

- If you do not have access to such a platform then first do not use an arbitrary rule. Let the data determine your click threshold. Second, look at data over a longer period of time. A short window can misdirect your efforts.

- Bucketing keyword data is useful as it gives you an understanding of where performance could be off-the head, torso or the tail.

- Avoid drastic actions like pausing words if they don’t meet your “good ROI” criteria, a gradual bid up /bid down approach is better.

- Finally, save yourself from the myth of “wasted” spend. If you sum all the keywords with clicks and no revenue you might think that you have “wasted” all this money on keywords that don’t convert. If you are seeing this data this way, then I would recommend pulling keyword reports from the previous time period and check what fraction of the keywords in the “wasted” bucket generated revenue in the previous period. The numbers might surprise you. Like I said before, the average number of clicks per conversion and the time period are critical to this analysis.

When you manage tail terms right, you can increase the performance of your marketing campaign, but it requires us to overcome our discomfort with sparse data and act in a patient, rational and statistically reasonable manner.

Contributing authors are invited to create content for Search Engine Land and are chosen for their expertise and contribution to the search community. Our contributors work under the oversight of the editorial staff and contributions are checked for quality and relevance to our readers. The opinions they express are their own.

Related stories

New on Search Engine Land