The Myths & Realities Of How The EU’s New “Right To Be Forgotten” In Google Works

Depending on what you read, a “Right To Be Forgotten” court ruling in the European Union this week means that now anyone can ask for anything to be removed from Google, which will soon collapse under an overwhelming number of requests. In reality, it’s far more limited than it sounds, though the ruling does raise […]

Depending on what you read, a “Right To Be Forgotten” court ruling in the European Union this week means that now anyone can ask for anything to be removed from Google, which will soon collapse under an overwhelming number of requests. In reality, it’s far more limited than it sounds, though the ruling does raise serious concerns. Here’s a Q&A on how things really will work, as best we can tell.

NOTE: Since this article was written, Google now has created a process for removals. See our follow-up story: How Google’s New “Right To Be Forgotten” Form Works: An Explainer

Is it true that anyone in the EU can have anything removed from Google and other search engines?

No. But anyone can ask to have things removed. That’s not a guarantee that it will happen.

How does someone make a removal request?

The court ruling simply says that they make this to Google or any search engine without giving specifics. Since this is so new, there have been no formal mechanisms established, in contrast to systems that Google (and other search engines) have for dealing with copyright infringement removal requests (commonly called DMCA requests).

Is the content entirely removed from Google and other search engines for all searches or just for someone’s name?

That’s unclear. It seems pretty likely to be tied to people’s names — that if you search on someone’s name, and they’ve had a right-to-be-forgotten censorship request upheld, then the listing won’t appear.

For example, say someone named Jamie Doe went bankrupt, and there was a newspaper article written about that which begins showing up in Google for searches for “Jamie Doe.” The listing for that article might get removed.

It’s not clear whether the search engines would be required to remove the listing for searches for someone’s name plus other words, such as “Did Jamie Doe go bankrupt?” It’s seems likely, but it’s not certain.

It’s more likely that the document can remain as long as you’re searching generically and not using someone’s name. For example, it might be OK to appear for a search on “bankrupt.” But again, we don’t yet know until some actual cases like this get acted upon.

I heard a pedophile already made a request to be “forgotten” in Google!

Someone who was convicted of having child pornography did make such a request. Google’s also had nine other requests that may make some question the wisdom of this new right, when balanced against the public’s right to know. We don’t know how these requests were made specifically to Google, but likely they came to Google though one of its many contact mechanisms. Read more in our article on Marketing Land:

Who decides if something will be removed?

It’s up to the search engine initially, but it can choose to reject a request. It is not required to simply remove anything someone wants taken down.

If the search engine rejects a request, is there an appeal process?

Yes, or at least government bodies that someone can turn to. The official EU court ruling summary says that if a search engine rejects a request, the person can appeal to a “supervisory authority or the judicial authority.” That seems to mean turning to either a privacy regulator or the courts of any of the EU’s member countries.

Will the government appeal always be upheld?

No. The court ruling says that information can’t be removed if it will interfere with the “preponderant interest of the general public in having, on account of its inclusion in the list of results, access to the information in question.”

So the EU says you have both a right to be forgotten and a right for people to find you?

Effectively, yes. This week’s ruling seems to give more weight to the right to be forgotten. But it acknowledges people in the EU have a fundamental right to also access information, and the language of the ruling suggests that either the search engines or the government bodies are supposed to balance these two rights against each other and make the correct call.

Can you give me an example of where the public would supposedly no longer need to know something about someone?

This ruling came about because a Spanish man objected that a listing about an auction of his property to cover debts owed to the state was showing up in Google. The state had ordered the auction be publicized in a newspaper so that, as the EU ruling says, it “was intended to give maximum publicity to the auction in order to secure as many bidders as possible.”

The newspaper notice that lead to the EU’s Right To Be Forgotten ruling

That 1998 newspaper article (really, a copy of an entire newspaper page with the notice) was showing up in Google long after the auction happened. That’s also long after the purpose for the order, to generate bidders for the auction, had ended. The main “purpose” was no longer needed, so there’s an argument that it being “forgotten” wouldn’t be harmful to the public in general.

Of course, there’s a counter-argument that the public might be served knowing that a particular person had a debt issue, especially if they were going to do business with them. That’s part of the balancing act that’s supposed to be considered now.

So Google will make these decisions?

If it was smart, it wouldn’t, except in very limited cases. Those cases might be the reasons where Google already makes such decisions, such as when social security numbers or credit card numbers are published online. Removing that type of information isn’t controversial. Making a judgment call on whether a story about someone convicted for having child porn is controversial.

But doesn’t Google have to make these decisions?

No, it does not. One strategy would be for Google (or any search engine) to decide not to decide. Any request it receives, it could respond that unless the request relates to some very specific situations, it will be rejected because Google doesn’t believe it can fairly judge between the right of privacy and the right of free speech. Instead, Google could recommend that someone go to a particular country’s privacy agency for a ruling and let that agency make the call.

Won’t the privacy agencies hate Google routing all requests to them for judgment?

Maybe, especially if they get overwhelmed by requests. But that’s not Google or any search engine’s problem. It’s the EU’s problem. An EU court ordered up this new right; that right includes the ability for a search engine to reject an initial request. Ultimately, it’s the privacy regulators or courts that have to make the call.

Won’t Google rejecting requests cause it to get bogged down in expensive legal cases?

Not necessarily. Google already rejects plenty of DMCA requests, if they’re not done properly. Google will only get bogged down in a legal case if wants to. If someone is sent to do an appeal, Google doesn’t have to turn up to fight its case against that person. It did that with the initial ruling because it didn’t want this type of “right to be forgotten” established in the way it was. But now that it has been, it doesn’t have to fight each and every case.

Doesn’t the information stay online, even if it’s removed from Google and other search engines?

Yes.

Isn’t that crazy? People can still find it!

They could, but not nearly as easily. That’s part of what the EU court seemed concerned about, that search engines make it easy to effectively pull together a profile on individuals in a way that might violate individual privacy rights. Removing links from Google and other search engines makes it much harder for this information to be found.

If something is removed from Google, is it automatically removed from other search engines like Bing?

No. Someone would have to make a request to each and every search engine they want material removed from, as best we can tell. The search engine also has to have some presence in an EU country. If it’s entirely outside the EU with no offices or servers there, it likely can ignore any requests.

What is a search engine, anyway? Could a newspaper web site with a search box be considered one?

The discussion in the ruling seems to consider search engines in the way ordinary people would, a service that collects information from third-party web sites and points back to them. It’s possible that someone may try to use this to block search results for any site that might have a search feature. There’s no guarantee they’d be successful.

If something is removed, is it removed for only a particular country version of Google or worldwide?

That’s unclear. With Google, in cases when it has been asked to remove material by a particular country, it typically responds by removing material only from that country’s particular edition of Google.

For example, if Google was told to take down content by a German court under that country’s laws that bar Nazi-related material, Google might remove the material from Google Germany (google.de). However, those who go to Google.com (even if they are in Germany) might still see it.

That’s also tended to satisfy EU courts and regulatory bodies in the past, perhaps because by default, Google tries to direct people outside the US to their own country-specific version of Google. Or perhaps the governmental bodies just don’t know any better.

Won’t what’s removed just show up on other sites, leading to a whole new request?

Maybe. It’s not uncommon for content on one web site to be copied to another web site, through both legal and illegal means. That’s one reason the EU court ruled the way it did, to make search engines responsible for removing links rather than requiring people to go to the publishers.

As it wrote: “It is possible that the same personal data has been published on innumerable pages, which would make tracing and contacting all relevant publishers difficult or even impossible.”

What’s not clear is whether Google is somehow going to be required to constantly check that some new copy of a web page previously removed doesn’t keep showing up. When it comes to DMCA requests in the US, publishers have to constantly watch for infringement and report it, even if it’s the same infringement over-and-over again, just on new web servers.

In Europe, both France and Germany have ordered that Google should be constantly monitoring to ensure certain pictures of former Formula One head Max Mosley do not appear in its results.

If Google or other search engines are ordered to do proactive removals, complying with the new law becomes much more difficult and likely to lead to false-positive removals, where content that shouldn’t be removed gets taken down.

Will Google be able to say if something has been removed?

It seems very likely that the ruling will not prevent Google from using a long-standing mechanism it has to tell searchers when it has been required to censor something from its results.

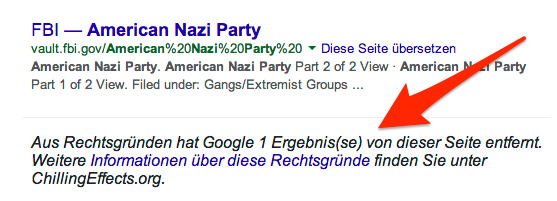

For example, in a search for “American Nazi Party” on Google, you get a notice like this, at the bottom of the page:

It says that in response to a legal request, Google has removed a page that would ordinarily have appeared. It also links over to the Chilling Effects site, where the order Google received is listed — though all the information in the order is redacted.

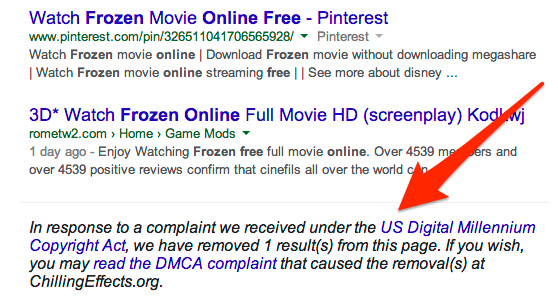

In a search on Google.com for “frozen online free,” Google has a similar notice alerting searchers that something has been removed:

In that case, you can read most of the removal request Google received, including the exact URLs that were pulled.

It’s possible that when Google ultimately removes material under the new right-to-be-forgotten ruling, it may still show a notice that something happened. Perhaps it might even be able to link over to the general order, where the curious may be able to ultimately hunt down the offending page outside of using a search engine.

Won’t these removals just make some of what’s being removed more noticeable?

It depends. The man whose case started this all — Mario Costeja Gonzalez — wanted to remove the link below that’s still appearing on Google Spain:

If you’re wondering why it’s still there, that’s because a Spanish court had originally rejected his request, leading to his appeal to the EU Court of Justice. The appeal found for the general right of removal, in some cases. In his specific case, he’ll now have to ask Spanish authorities if they’ll order Google to do so, under this new right.

Ironically, they might say no because his entire fight might have made that link suddenly relevant and not in the public interest for removal, especially now that there are so many articles out there covering what it was about. Even if he gets it removed, the other articles are likely to remain.

Other people who initially fight for removal of content might find the same thing happens to them, especially if they lose. Potentially, news might emerge about their efforts, making what they hoped would be forgotten remembered afresh.

But many others likely needn’t fear this. If they aren’t public figures, and what they hope to have removed has largely been forgotten except likely by them, when they ego search their own names, then the removal may work.

Tell me more!

We will, as more is known. From the major search engines, Bing isn’t commenting at all. As for Google, it told us:

The ruling has significant implications for how we handle takedown requests. This is logistically complicated – not least because of the many languages involved and the need for careful review. As soon as we have thought through exactly how this will work, which may take several weeks, we will let our users know.

The Guardian has a good Q&A about the new right that’s also well-worth reading. At the New York Times, Jonathan Zittrain argues against the ruling. CNN has a First Amendment attorney arguing in favor of it.

You can read the ruling itself here, though the official press release (PDF) from the court is easier to digest.

And as mentioned earlier, our 10 People Who Want To Be Forgotten By Google, From An Attempted Murderer To A Cyberstalker article on Marketing Land has examples of real requests we’ve learned that Google has received.

NOTE: Since this article was written, Google now has created a process for removals. See our follow-up story: How Google’s New “Right To Be Forgotten” Form Works: An Explainer

Contributing authors are invited to create content for Search Engine Land and are chosen for their expertise and contribution to the search community. Our contributors work under the oversight of the editorial staff and contributions are checked for quality and relevance to our readers. The opinions they express are their own.

Related stories

New on Search Engine Land