Study: Google “Favors” Itself Only 19% Of The Time

For the past year or so, there’s been a rising meme that Google is altering its search results in ways to favor itself over competitors. Now a new study is out showing the opposite. Google is far more likely not to show its own products in the first spot of its search results. The survey […]

The survey is from Ben Edelman, an assistant professor at the Harvard Business School. Edelman is a long time Google watcher who regularly publishes interesting and detailed looks at search and advertising-related topics. Edelman has also consulted for Microsoft and is involved in a lawsuit against Google.

Edelman reaches completely different conclusions from his survey than I do, writing at the end:

By comparing results across multiple search engine, we provide prima facie evidence of bias; especially in light of the anomalous click-through rates we describe above, we can only conclude that Google intentionally places its results first.

How have we ended up with such different conclusions? Why, I love Google, of course — and he clearly hates them! Seriously, statistics can easily be turned to whatever you want them to be. I feel like Edelman is turning his study into the most negative view possible. I’m just looking to provide some balance to that.

The Study

Edelman’s study is clever (and one I’m pretty sure has been done a few years ago by others). Search for products that Google offers, and see whether Google lists it own products over those of competitors. Searches included things like:

- calendar

- chat

- maps

- video

The study did this, for 32 different searches at Google, Yahoo and Bing, back in August 2010.

The Age Issue

Immediately, the age of this testing is a problem. Back in August, Yahoo was still providing its own results. Today, it’s powered by Bing. The study provides no conclusions about what’s happening on Yahoo, right now.

In addition, results change all the time. For some of these queries, I get different results at either Google, Bing or both versus what the study reports. In short, this study says nothing about about the current state at any of these services.

I asked Edelman about this, via email. He agreed, saying:

Your reference to the age of our data is well-taken. When we started the process, we intended to get this paper out quite a bit faster. It’s easy enough to redo the results with the newest data; we can, and perhaps we will, depending on response to this piece. But incidentally, it’s also useful to preserve results as they were a few months ago. That will certainly be important in disputes: Folks will be discussing not just what results appear now, but also what was done in the past.

Sure, but a single historic data point still doesn’t necessarily prove anything. As I emailed back:

I agree it’s interesting to know what the results were six months ago for historic reasons, but that’s also just one data point. They might have been much “worse” in terms of Google’s supposed favoring six months before that. Or much less.

The Small Sample

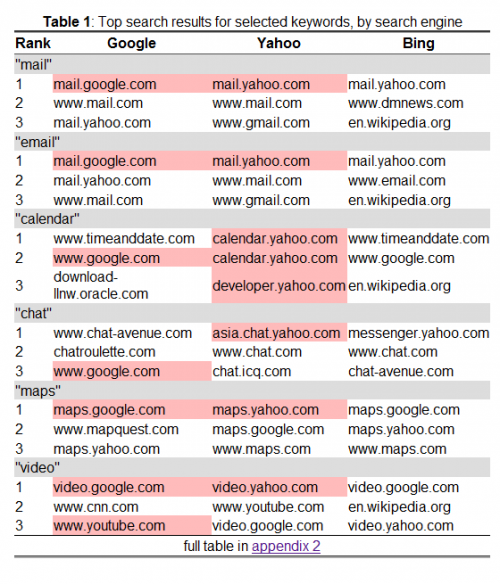

Edelman’s report prominently features a chart that highlights in red how Google apparently favors itself in the top three listings for various terms:

Look at all that red, which indicates when a search engine supposedly favored itself. All that red must make it true! And for Yahoo, too!

Still, drawing a conclusion from only six queries would be foolish. The report is primarily based on a list of 32 searches, which are listed on a separate page. Using the full list, it’s easy to find a chunk that doesn’t portray Google as full of red favoritism:

Even looking at the “larger” sample of 32 queries, it’s still a relatively small dataset. More important, it doesn’t correct for the popularity of the particular services.

Probability Versus Popularity

There’s a section of the report where Edelman talks about doing some regression analysis to disprove that the favoritism that he alleges is just random.

Look, just because someone says they’ve done a regression analysis doesn’t mean that something is statistically correct — even if it sounds that way. The fundamental structure of the test itself might be flawed. If so, all the analysis you do isn’t going to correct for that.

Edelman’s study assumes that any time Google puts one of its own services first, that’s somehow favoritism rather than a reflection of how important the service is in general.

For instance, using Edelman’sown data, there were five instances I found where both Google and Bing put Google’s services in the top position:

- books

- images

- maps

- translate

- video

Crazy — Bing putting Google Maps first! Is it a plot by Microsoft to try and prove how unbiased that it is? Or is it perhaps a reflection that a lot of people use Google Maps — and thus link to it — which in turn can influence the search results at both search engines?

If you wanted to do a really scientific study of “favoritism,” you’d first calculated the relative popularity of each service. Then you might first try to determine if the service is being listed in the order you believe it “should” appear at. If Yahoo Mail is the most popular email service on the web, and Gmail the second, then do they get listed in that order?

Even then, I still think you have issues. Popularity doesn’t always equal relevancy. But I definitely know that, regression analysis aside, there are underlying problems that make these stats suspect.

Search Algorithms Don’t Agree

One of the biggest problems I have with the report is when Edelman writes:

Taking seriously the suggestion that top algorithmic links should in fact present the most relevant and useful results for a given search term, it is hard to see why results would vary in this way across search engines.

It’s not hard to see why search engine result differ at all. Search engine each use their own “algorithm” to cull through the pages they’ve collected from across the web, to decide which pages to rank first. The articles below explain more about this:

- Schmidt: Listing Google’s 200 Ranking Factors Would Reveal Business Secrets

- What Social Signals Do Google & Bing Really Count?

- Google: Now Likely Using Online Merchant Reviews As Ranking Signal

- Dear Bing, We Have 10,000 Ranking Signals To Your 1,000. Love, Google

Google has a different algorithm than Bing. In short, Google will have a different opinion than Bing. Opinions in the search world, as with the real world, don’t always agree.

Indeed, there have been many studies over the past years that have found search results often do not agree. Another reason for this is that the core collection of documents — the “index” — that search engines search through are not exactly the same.

Google Searchers Aren’t Bing Searchers

One factor that both search engines assess is clickthrough. Bing has explicitly said that the number of clicks a listing gets is one of many factors it considers. You can imagine that something listed in the top position would be expected to get a certain percentage of clicks. If it doesn’t, that can be a sign that maybe something else should be there, because searchers are bypassing it.

Google also measures clickthrough. What you click on is used to help personalize the results you see, even if you’re not logged in at Google. My assumption is that Google also uses clickthrough generally for non-personalized results, thought it hasn’t confirmed this.

In either case, clickthrough is not the most important ranking factor. It’s just one of many of them. But it can have an influence. In turn, that might help explain some of the “favoritism” that Edelman saw. If someone’s searching for “maps” on Google, they may be more likely to want Google Maps than Yahoo Maps — and vice versa.

If clickthrough is helping measure this, is that favoritism — or is that ensuring your search algorithm is working best for your particular audience?

So Why’s Yahoo Mail Second?

Edelman did try to account for the potential clickthrough factor, and it’s perhaps the most intriguing part of his report. He used two different sources to gather clickthrough rates on Google, Yahoo and Bing. For email, he found that Gmail was listed first on Google and pulled 29% of the clicks versus Yahoo coming second and getting 54%.

That’s odd. It suggests that searches on Google aren’t being well served by that search — and Edelman counts it as further proof that Google is favoring itself. Then again, it could be….

- Visitors click to Yahoo, don’t want that and immediately come back to Google’s results, something Edelman tells me he didn’t measure

- Lots of searchers were looking for Gmail and realized they could get to it another way after doing the search

- Google’s results are screwy. Google, like all search engines, has screwy results for all types of things

It is intriguing, but that’s also apparently the most damning part of the clickthrough analysis that Edelman could find.

In general, he says only “sometimes” does the second results listed get more clicks than the first. Apparently, it doesn’t happen the majority of times. It would have been useful for him to have shown how many times each service listed itself first and had clickthroughs that supported that.

Hey, Who’s Ranking For “Search Engine?”

Now if you really want to crank up the conspiracy theories, let’s talk about Google’s most important product, search.

Google offers a search engine, just like it offers email, chat and other products. That search engine is still Google’s most important and profitable product, to my knowledge. So what do I get in a search for search engine on Google?

Google doesn’t list its search engine at all. Yes, Google is finally at least getting a spot as a company by having its Google Custom Search service appearing here — but that’s a completely different product that the consumer oriented search engines that it does list like Dogpile, Bing, AltaVista, Ask.com, Yahoo and even tiny Duck Duck Go.

Seriously — Google can’t list Google.com but manages to get Duck Duck Go into its top results? It makes no sense. Having watched this results set for literally years, I’m borderline believing that rather than favoring itself, Google is deliberately downgrading itself here, as a way to show the world how it doesn’t favor itself.

But Google Admits Favoritism!

At the end of the report, Edelman tries to turn a comment by Google’s Marissa Mayer — made when she was vice president of search product and user experience — as further evidence that Google is tampering with its results, as if this further confirms his findings:

At a 2007 conference, Google’s Marissa Mayer commented:

“[When] we roll[ed] out Google Finance, we did put the Google link first. It seems only fair right, we do all the work for the search page and all these other things, so we do put it first… That has actually been our policy, since then, because of Finance. So for Google Maps again, it’s the first link.”

We credit Mayer’s frank admission, and our analysis is consistent with her description of Google’s practices. But we’re struck by the divergence between her statement and Google’s public claims in every other context.

Edelman’s report is about Google’s “algorithmic” results, the “10 blue links” as they’re sometimes called — the meat of the page. Mayer wasn’t talking about algorithmic results. She was talking about Google’s OneBox units, where Google shows results from its various vertical search engines.

Edelman disagrees. From our email exchange:

Look at that last sentence: “For Google maps again, it’s the first link.” “For Google maps again” – that must mean, when a user runs a map-related searches, like “Boston map” or maybe “Boston museum.” But “it’s the first link”? There was never going to be more than one map embedded on the page. Nor, to my knowledge, has Google ever run a map rich result box that linked to multiple different map services. (In contrast, as Marissa mentions, finance rich result boxes do link to multiple finance sites.) So what does Marissa mean when she says “It’s the first link”? I think she means all the other maps sites drop to lower algorithmic search links; Google puts its map service at the top and others below. And others are indeed ordinary algorithmic results, not any kind of special rich result or onebox result.

No, Google Doesn’t “Admit” That

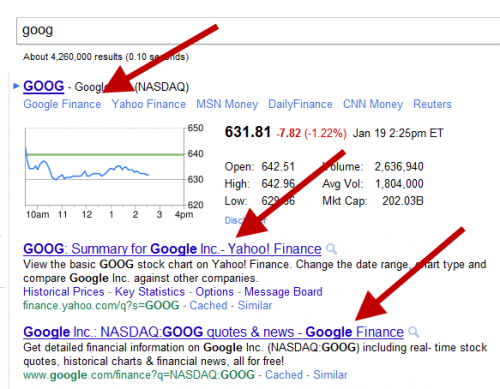

It’s pretty easy to know exactly what Mayer meant. You can watch her answer yourself here at 44:51 seconds into her talk. She’s talking about the first link in the list of sites that appear when you do a stock search on Google and get a OneBox result. Google puts itself first on that list:

See the first arrow? It points to a list of sites that appeared under the current stock price for Google, when I did a search for goog, the Google stock symbol. Mayer was saying that before Google Finance was launched in 2006, links there were ordered by popularity. But after it launched its own service, Google thought it was fair to list itself first on that line.

Look at the second arrow. That’s the first “algorithmic” result that Edelman’s report covers and which he says Mayer’s comment is about. It’s not about that, at all. Indeed, that first algorithmic link goes to Yahoo Finance — not Google Finance. Google Finance comes second in the algorithmic listings.

Beyond The Algo Listings

Talking about the algorithmic listings as if they are somehow independent of the rest of the search page is kind of absurd, of course. Studies have found that they tend to be the results that attract the most clicks. But the days of search results that are only 10 blue links are long gone. People might interact with OneBox and other smart answers that ALL major search engines have long provided.

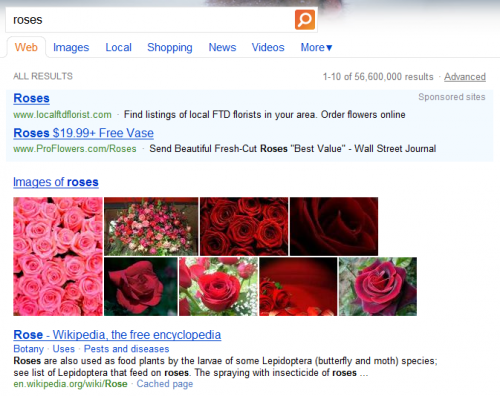

Is it unfair for Google to “favor itself” by showing me images from its own image search engine rather than Bing’s, as it does here:

Or does that just make sense — that Google also has an image search engine, and it should point people to that? Certainly, Bing does the same:

To me, it just makes sense for Google or any search engine to point to its vertical search engines if it runs them. They obviously believe they have good results for their users there. For them to not to would be like complaining that the New York Times continues to run its own entertainment section rather than including the entertainment section from the Los Angeles Times.

For more on this topic, see these past posts:

- Once Again: Should Google Be Allowed To Send Itself Traffic?

- The Incredible Stupidity Of Investigating Google For Acting Like A Search Engine

- The New York Times Algorithm & Why It Needs Government Regulation

- Mr. Cutts Goes To Washington, Testifies Google Has Integrity

- Deconstructing “Search Neutrality”

Measuring Fairness

Still, some are going to want to measure whether Google is somehow favoring itself. So what do you measure?

Do the “rich” OneBox style results count? Do you count only unpersonalized results, despite the fact that “normal” results these days on Google means personalized results (see Google’s Personalized Results: The “New Normal” That Deserves Extraordinary Attention).

Do you count the things that Edelman’s report considered? Whether Google lists any pages from itself in its top results, or just the top three listings, or whether Google itself first above all else?

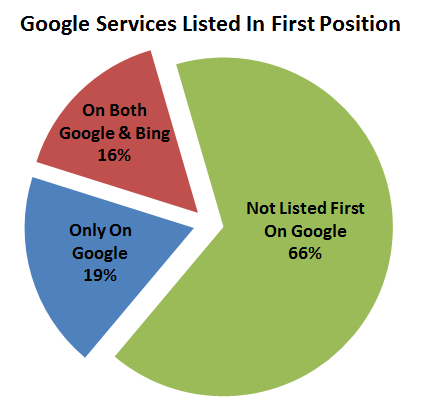

To make sense of Edelman’s figures, I tried to keep it simple. I went to his full list of 32 searches that were conducted. I found that there were 11 searches in total where Google listed itself first above all others. I then looked to see in which of these cases that Bing also listed Google first. That happened five times, which I mentioned above. That left these six searches where Google — and only Google — “favored” itself

- academic article

- blog

- finance

- scholarly journals

So in 6 our of 32 cases, Google would seem to have favored its own products in a way that might raise eyebrows – 19% of the time. After all, if Bing’s going to list Google first in those other cases, counting these “against” Google doesn’t seem fair.

Even in these cases, the stats still don’t reflect that competitors may be very visible. Even if Google listed itself first for “email” — however it happened — is it really anti-competitive when its competitor is prominently listed in second place? Wouldn’t it really be more of a concern if Google didn’t list its competitors at all?

Google’s Response

Shortly after I published this, I also received an unsolicited statement from Google (it will commonly send statements around to journalists, if a story or study is making the rounds. Here you go:

Mr. Edelman is a longtime paid consultant for Microsoft, so it’s no surprise that he would construct a highly biased test that his sponsor would pass and that Google would fail. Google never artificially favors our own services in our organic web search results, and we perform extensive user testing to ensure that search results are ranked in a way that provides users with the most useful answer.

Google also sent some examples that contradict the idea that Google favors itself. Among them?

- search engine

- book flights

- directions

Hey, didn’t I mention that search engine example! Indeed, I did – along with some other things that Google is pointing out, such as taking the popularity of services into account or what searchers at particular services might prefer.

We Want Relevancy, Not Regulation

A search engine’s core algorithm results have long been seen in some quarters as “editorial” content that shouldn’t be tampered with to favor anything other than what’s best for the searcher. Not every search engine has followed this practice, of course. In my experience, Google has been the best at it, refusing to fix things by hand even when it should (see Google, Bing & Searching For The New Wikileaks Website).

I have a great fear of governments stepping in to dictate what a search engine’s listings should be. To me, that’s akin to telling a newspaper what it can report on, or trying to regulate opinions anywhere. There are no “perfect” search results, nor will you ever find a set that’s “neutral.” An algorithm, ultimately, is an opinion. Opinions are not neutral.

What we really should be concerned with isn’t whether Google (or any search engine) is being “fair” but rather if it is providing relevant answers. I can remember when Lycos favored itself so much back in the late 1990s that it was difficult to do a search that didn’t lead you back into Lycos.

Where’s Lycos today? Right. Relevancy will attract and retain users. If Google or any search engine isn’t providing relevant results, the market will likely correct things. And in fact, that’s what a recent survey found. People are far more concerned about getting more relevant results than government regulation of results. See the two articles below, for more on this:

Contributing authors are invited to create content for Search Engine Land and are chosen for their expertise and contribution to the search community. Our contributors work under the oversight of the editorial staff and contributions are checked for quality and relevance to our readers. The opinions they express are their own.

Related stories

New on Search Engine Land