Once Again: Should Google Be Allowed To Send Itself Traffic?

The question of Google’s right to refer traffic to its own sites is once again in the center of policy debate. The European Commission is looking at this issue as part of its larger anti-trust investigation against Google. It’s also a question at the heart of the federal regulatory review of the ITA acquisition. Preferential […]

The question of Google’s right to refer traffic to its own sites is once again in the center of policy debate. The European Commission is looking at this issue as part of its larger anti-trust investigation against Google. It’s also a question at the heart of the federal regulatory review of the ITA acquisition.

Preferential treatment in search

This weekend a story appeared in the Wall Street Journal (others are in the works) that features a number of web CEOs complaining or expressing concern about Google giving “preferential treatment” to its own properties:

Google Inc. increasingly is promoting some of its own content over that of rival websites when users perform an online search, prompting competing sites to cry foul.

The Internet giant is displaying links to its own services—such as local-business information or its Google Health service—above the links to other, non-Google content found by its search engine.

When someone searches for a place on Google, we still provide the usual web results linking to great sites; we simply organize those results around places to make it much faster to find what you’re looking for. For example, earlier this year we introduced Place Search to help people make more informed decisions about where to go. Place pages organize results around a particular place to help users find great sources of photos, reviews and essential facts. This makes it much easier to see and compare places and find great sites with local information . . .

As Susan and Udi wrote, we built Google for users, not websites. We welcome ongoing dialog with webmasters to help ensure we’re building great products, but at the end of the day, users come first. If we fail our users, competition is just a click away.

There are many complicated technical and philosophical questions raised by this discussion, which has come up periodically over the years. If you take the position that Google is a “utility” that can make or break publisher sites because, as a practical matter, there is no competition in search you reach very different conclusions than you would if you see Google as one competitor among many. Hence the familiar refrain, repeated in the Google blog post, is “competition is just a click away.”

Accordingly there are major legal and policy implications depending on how Google is “defined.”

The problem of “search neutrality”

Would search engines need to rectify imbalances by offering privileged status to certain types of results? This would bring a massive outcry.

The concept of “search neutrality” has been invoked by Google opponents to argue that Google shouldn’t be permitted to favor its own properties (or by implication change its algorithm). This shows up in the WSJ piece:

This fall, Google made its links to its millions of Place pages even more prominent on the first search results page, pushing sites such as TripAdvisor.com farther down the page for searches on “Berlin hotels,” for instance. Place pages for businesses give basic information such as location and hours as well as a summary of user-generated reviews from sites like Citysearch and Yelp. Carter Maslan, a Google product management director, acknowledged “a little bit” of tension between Google and local-information sites. But he said the changes are meant to improve users’ experience by getting them more information about businesses faster, and to provide links to review sites.

Upset over lost traffic

To some degree this is about publishers “settled expectations” and changes in the Google algorithm disrupting them: “we’re getting less traffic than we used to.” As the WSJ piece points out Bing operates in a way that is similar, often referring traffic to its own sites. In the broader context of the evolution of search all the engines, Yahoo included, have been moving toward “answers not links.” That means more structured content on page one of SERPs and less clicking through to third party sites.

Publishers might argue that there isn’t a “level playing field” and Google has a competitive advantage vs. others. There’s truth in that argument but if it were entirely correct wouldn’t every one of Google’s products “win” its segment? That hasn’t been the case. Google has many under-performing products.

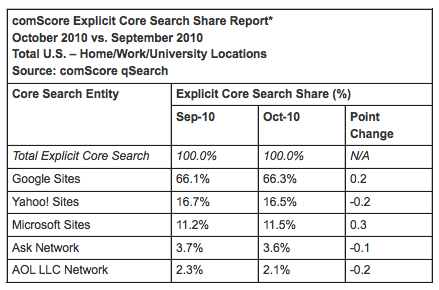

But because online search is the “gateway to the internet” and because Google “owns” more than 65 percent of query volume in the US (more in some EU countries) it’s not unreasonable to debate these questions. Yet Yahoo and Bing, combined, have a meaningful 28 percent of search volume. Isn’t that competition — or is that a “duopoly”?

In technology you can’t really regulate a competitive market into existence though you could potentially help restore competition to one out of balance. You’re ultimately seeking to ensure choice and prevent pricing distortions that may impact end-users (consumers, advertisers). Those values don’t seem to be implicated in this discussion. Competing CEOs might argue that long term there’s less choice if their sites go out of business. But you can’t make an argument that your site is entitled to position 1 or 2 (and so on) in SERPs.

Mapquest executives will argue that Google’s ability to refer traffic to itself is what helped Google Maps topple the long-time mapping leader from its number 1 spot two years ago. Yes, Google did send traffic to its own maps. However the answer is not that simple; the Google product was better than Mapquest. The latter had been complacent for several years due to management distractions at TimeWarner and didn’t invest in the product until relatively recently.

What are Google’s obligations to others?

Does Google have a right to offer its own content and products at all? That question is lurking in this discussion. Most people would say “yes.” The question then quickly becomes: can Google send traffic to its own mapping or product search or video or news sites? If you say “no” then what does that mean in practice? Does Google need to remove all references to its own products from organic results?

Alternatively should Google’s own products be in some fixed position on the page below other publishers? What are or should be Google’s “obligations” to third party publishers? This is the central question it seems to me.

These are all very difficult issues and become extremely problematic at the level of execution. If regulators start intervening in Google’s ability to control its algorithm and its own SERP it sets a bad precedent and compromises Google’s ability to innovate and maybe even compete over time. However I’m not trying to dismiss concerns about Google’s power and impact on the market. There are no easy regulatory answers at the level of the SERP.

In the case of the map-pack/0-pack/x-pack, one of the scenarios raised in the WSJ piece, Google often sends traffic directly to local websites rather than to publisher-aggregators, which used to get that traffic.

One used to see huge amounts of travel-affiliate spam in SERPs on Google. Queries like “Sheraton, New York” brought up numerous affiliate directories before the hotel site itself. Google addressed that, cleaned up the pages, and delivered a better user experience. Very few people would want to go back to affiliate travel spam. (I’m not talking about sites like Kayak or Orbitz.)

What if the Google Places Page or Shopping or Maps actually do offer a better experience than the sites of those voicing criticism? This is subjective but Places Pages often do offer a better user experience than many of the local competitors in the market.

Being a public company compels Google to chase new markets

The notion that Google should be nothing more than a shell or traffic hose is flawed; it’s also a fantasy. Google is a public company looking for growth. It will continue to expand, pursue its own interests and improve its products in areas where it sees opportunity.

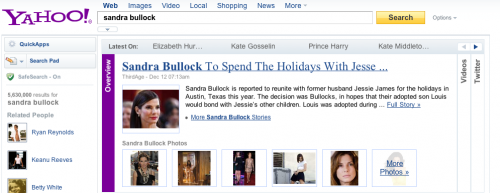

Google shouldn’t be permitted, it seems to me, to manipulate search results to punish specific publishers or competitors. In addition, one might argue that Google shouldn’t be permitted to consistently reserve the top organic position in organic results for its own sites. But this is precisely the case with “onebox” and “smart answers” and comparable offerings across all the engines. Yahoo offers the most elaborate of these with its “accordion” smart answer:

It has also been held by courts that the content of SERPs is an “editorial” arena protected by the First Amendment. So hypothetically Google could only show Google-related results and still be within the law.

It must also be said that Google is not the only way for companies to get exposure in the market. Publishers and site owners got used to “free” traffic from Google SERPs and have developed a kind of “vested interest” in that traffic. But any one site is no more “entitled” to traffic than any other site. By contrast, the only place right now where I do see facts that raise potential anti-competitive concern arise out of the Skyhook-Google litigation. But that suit is in process and all the facts not out.

Google’s dominance of the market may decline in a few years. I’m not a laissez-faire, free-market lover but the market may take care of itself. Facebook and others are working on ways to discover content that don’t require conventional search-engine usage. Indeed Google is quite concerned about this, which is why it’s working so diligently on an improved “social” strategy.

The powerful will always be tempted to utilize their power for unfair gain. The duty of regulators is to keep markets fair and functioning for the good of the larger system and society. When any single company becomes too powerful or gains too much control over a market segment governments should look carefully to see if any manipulation or bad behavior is going on.

However in my mind the Google Places algorithm doesn’t qualify.

Also see our previous piece related to this topic, The Incredible Stupidity Of Investigating Google For Acting Like A Search Engine.

Contributing authors are invited to create content for Search Engine Land and are chosen for their expertise and contribution to the search community. Our contributors work under the oversight of the editorial staff and contributions are checked for quality and relevance to our readers. The opinions they express are their own.

Related stories