Duck Duck Go’s Post-PRISM Growth Actually Proves No One Cares About “Private” Search

Look out, Google! Duck Duck Go is on the rise, posting a 50% traffic increase in just eight days. Is this proof people want a “private” search engine, in the wake of allegations the PRISM program allows the US government to read search data with unfettered access? Nope. Google has little to worry about. People don’t […]

Look out, Google! Duck Duck Go is on the rise, posting a 50% traffic increase in just eight days. Is this proof people want a “private” search engine, in the wake of allegations the PRISM program allows the US government to read search data with unfettered access? Nope. Google has little to worry about. People don’t care about search privacy, and Duck Duck Go’s growth demonstrates this.

Don’t get me wrong. If you ask people about search privacy, they’ll respond that it’s a major issue. Big majorities say they don’t want to be tracked nor receive personalized results. But if you look at what people actually do, virtually none of them make efforts to have more private search.

Duck Duck Go’s growth is an excellent case study to prove this. Despite it growing, it’s not grown anywhere near the amount to reflect any substantial or even mildly notable switching by the searching public.

Duck Duck Go’s Growth, In Perspective

Duck Duck Go maintains a traffic page where anyone can see how it has grown, and in the last few days, it’s been dramatic:

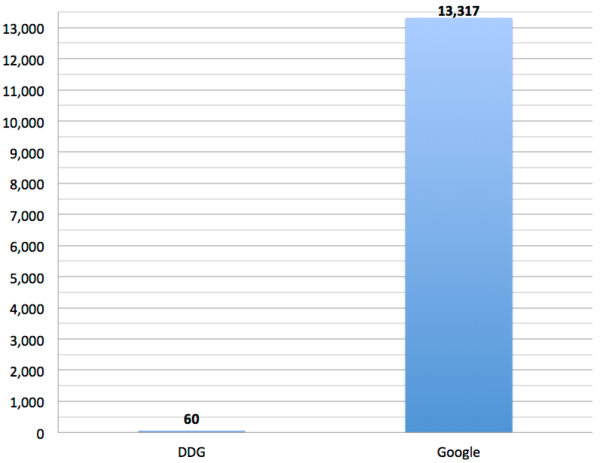

Using that data, here’s Duck Duck Go’s traffic versus Google before the PRISM news came out:

That’s taking Duck Duck Go’s 2 million searches per day that it was at just before the PRISM news broke on June 6. Actually, Duck Duck Go had come close to but never actually reached 2 million searches per day before PRISM. That happened four days after the news came out. But it’s close enough for the purposes of this article. Duck Duck Go was at 2 million searches per day, or 60 million searches per month. That compares to 13,317 million searches per month — 13.3 billion — for Google.

I’ll explain more about those Google figures in a bit. But next, here’s the post-PRISM change, where 11 days after the PRISM news broke, with even more revelations of the US National Security Agency spying, Duck Duck Go cracked the 3 million searches per day mark, putting it on course for a 90 million searches per month. How’s all that new growth compare to Google?

In comparison to Google, Duck Duck Go’s growth might as well not even count. It’s nowhere near close. It’s not close to Bing or Yahoo, either. At 90 million searches per month, Duck Duck Go still needs to triple that figure to reach the search traffic of AOL, 266 million per month, according to comScore.

That’s also not counting any worldwide traffic AOL has. Similarly, that 13 billion figure that Google handles is only for searches in the United States, whereas Duck Duck Go’s data is for worldwide traffic. And while the Google traffic is for May 2013, and so potentially doesn’t reflect any post-PRISM loss, it’s pretty clear from Duck Duck Go’s figures that hundreds of millions of people haven’t left Google for it. Tens of millions haven’t. Maybe, at best, one million have.

People Don’t Actually Seek Out Private Search

Over the past few weeks, I’ve done several press interviews about Duck Duck Go, where the issue of whether it can beat Google by being more “private” has come up. My answer has consistently been “no,” because that’s been the experience of search engines before that have tried this.

I can imagine some on Reddit or Hacker News or elsewhere arguing about how this time, it’s different. This time, with all the NSA allegations, privacy is front and center. This is the right time for a private search engine to emerge.

I doubt it. Having covered the search engine space for 17 years now, having seen the privacy flare-ups come-and-go, I’d be very surprised if this time, it’s somehow going to cause more change than in the past.

Past Privacy Moves

Here’s a good example. Back in 2007, Google decided it would start to anonymize its search data. After 18-to-24 months, Google said it would break connections between what was searched for and particular IP addresses, to increase privacy. It wasn’t forced to do this. It wasn’t a reaction because some government body sent it a letter. Google itself decided that was a good, voluntary move to help increase privacy.

In response to this, the European Union decided that Google voluntarily cutting its search data retention policy from forever to two years wasn’t enough. Its main privacy body jumped in demanding data be retained for even less time, without even understanding other EU regulations prevented this.

That fracas kicked off an industry competition to be more private. Sensing a weakness where it might win against Google, Microsoft declared it would anonymize data after 18 months. Yahoo said it would cut retention to only 90 days. Ask launched Ask Eraser, promising instant privacy, for those who wanted it.

All this happened in an environment where there was much media focus on search privacy. How’d it work out? None of the Google competitors trying to win with a “private” feature made any impact on Google’s share. Yahoo rolled back and starting keeping data up to 18 months. Even Startpage, based out of Europe and with a long-time focus on promising private searching, found its efforts in 2009 didn’t pay off. It took until now for Startpage to get to 3 million searches per day.

The Privacy Google Already Provides

That was then, this is now? Microsoft has been spending millions on its “Scroogled” attacks on Google since late last year, viewing privacy as “Google’s kryptonite.” So far, that kryptonite not has any measurable impact on the Search Engine Of Steel.

Sure, there’s always the chance that this time, it’s different. That this time, people will decide that search privacy is so important that they do abandon Google, Bing and Yahoo for tiny, virtually unknown search engines that haven’t been named in allegations that they somehow provide easy, direct and unfettered access to search data — allegations the major players have all denied.

Maybe Duck Duck Go and Startpage will be seen as somehow “safer” options by the masses, even though that also means people have to trust that the NSA isn’t somehow breaking the encryption that Duck Duck Go and Startpage use — something that Google also uses.

Google is protecting privacy? Yes. Since October 2011, Google has moved to encrypt more and more of the searches that happen on its site, even if the searchers themselves haven’t thought about this or requested it. Millions more have been protected by this move than have ever used Duck Duck Go or Startpage.

In fact, when Duck Duck Go claims on its Don’t Track Us privacy site that when people search on Google that “your search term is usually sent to that site,” there’s an excellent chance now that this usually not the case at all. Publishers who have seen the rise of “Dark Google” and “not provided” in their analytics knows that Google’s encryption has kept much data from flowing out.

Google, of course, does retain the data internally, unless people switch off search history or purge it from time-to-time. That means Google can use it in various ways, including ways that help improve searches. That also means it’s available if Google is served with a legal request to deliver it. It also means, if you want to believe the PRISM allegations, that the NSA has a direct line into everything happening at Google. Again, that’s something that the company has continued to deny.

As For Duck Duck Go

Don’t get me wrong about Duck Duck Go. I love that there’s a plucky little competitor out there like it, just like I’m happy to have Blekko out there, which actually does more “heavy lifting” in search by indexing the web rather than relying on the search results from others.

Duck Duck Go, which got funding at the end of last year from Union Square Ventures, has done an outstanding job of punching above-its-weight in attracting press attention. It has also rightfully helped focus attention on privacy issues that people should be aware of, so they can make informed decisions. That type of pressure can help improve the major players, in compelling change.

But being a darling of media stories has only translated into one search engine that I know of becoming a real giant. That was Google. Google got there in large part because of a serious investment in core search infrastructure.

Duck Duck Go is relying on results largely from other search engines, with a smart algorithm to sort through those answers and a privacy pitch, to go up against a company that actually harvests information directly and can literally can have a conversation with you because it understand more than matching word patterns.

AOL Search might be endangered by Duck Duck Go, and that’s an impressive achievement. And Duck Duck Go, with limited staff and expenses, might make it as a profitable business. But I just don’t see it as a serious threat to Google, even with the current privacy climate. Search privacy as a selling point hasn’t worked before; I’d be surprised if it works now.

Related Articles

- Pew Report: 65% View Personalized Search As Bad; 73% See It As Privacy Invasion

- Google Anonymizing Search Records To Protect Privacy

- Microsoft To Anonymize Log Data; Calls For Industry Standards Along With Ask.com

- Yahoo One-Ups Google With 90 Day Data Retention Policy

- Yahoo Search Data Retention Goes From 90 Days To 18 Months

- Google’s Impressive “Conversational Search” Goes Live On Chrome

- Yahoo: We Take User Privacy Seriously Too!

- Google Makes First Amendment Challenge To Publish FISA Request Counts

- Google: Government Has No Back Door, Front Door Or Side Door To Our Data

Contributing authors are invited to create content for Search Engine Land and are chosen for their expertise and contribution to the search community. Our contributors work under the oversight of the editorial staff and contributions are checked for quality and relevance to our readers. The opinions they express are their own.

Related stories