Google’s site reputation abuse policy is a band-aid for a bullet wound

Dive into the challenges of parasite SEO and why Google’s algorithmic shortcomings make this policy a temporary fix for a systemic issue.

Google’s updated site reputation abuse policy attempts to tackle a growing issue in search: large, authoritative sites exploiting their domain strength to rank for content they don’t own or create.

While the policy is a step in the right direction, it doesn’t address the underlying systemic problems with Google’s algorithm that allow this abuse to thrive.

Understanding Google’s site reputation abuse policy

Google’s site reputation abuse policy was introduced in March 2024, but its announcement was overshadowed by a major core update that same month.

As a result, what should have been a pivotal moment for addressing search manipulation was relegated to a footnote.

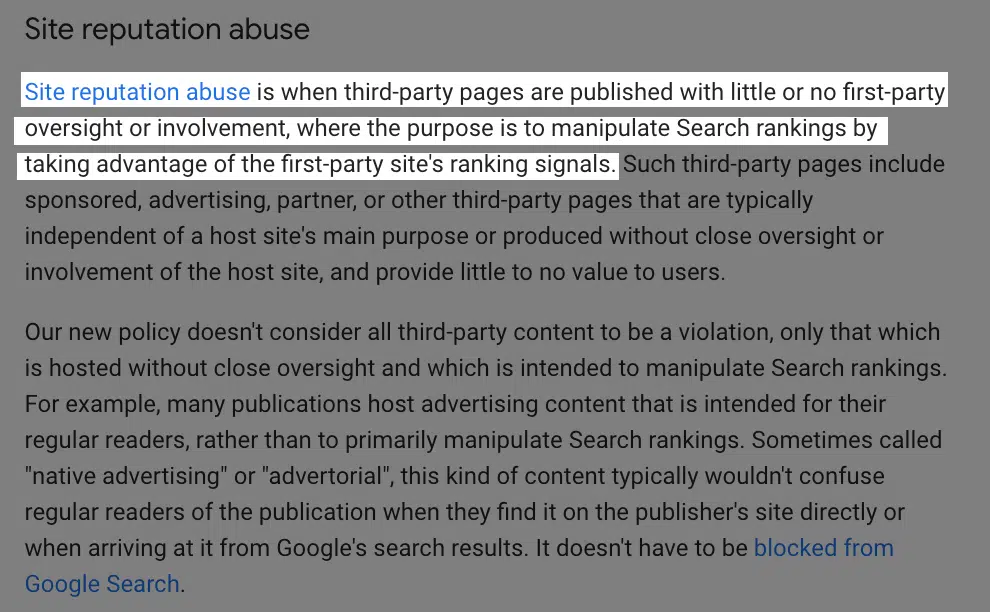

At its core, the policy targets large, authoritative websites that leverage their domain strength to rank for content they didn’t create.

It’s designed to prevent these entities from acting as “hosts” for third-party content simply to exploit search rankings.

A clear example would be a high-authority business site hosting a “coupons” section populated entirely with third-party data.

Recently, Google expanded the policy’s scope to address even more scenarios.

In the updated guidelines, Google highlights its review of cases involving “varying degrees of first-party involvement,” citing examples such as:

- Partnerships through white-label services.

- Licensing agreements.

- Partial ownership arrangements.

- Other complex business models.

This makes it clear that Google isn’t just targeting programmatic third-party content abuse.

The policy now aims to curb extensive partnerships between authoritative sites and third-party content creators.

Some of these often involve deeply integrated collaboration, where external entities produce content explicitly to leverage the hosting site’s domain strength for higher rankings.

Dig deeper: Hosting third-party content: What Google says vs. the reality

Parasite SEO is a bigger issue than ever

These partnerships have become a significant challenge for Google to manage.

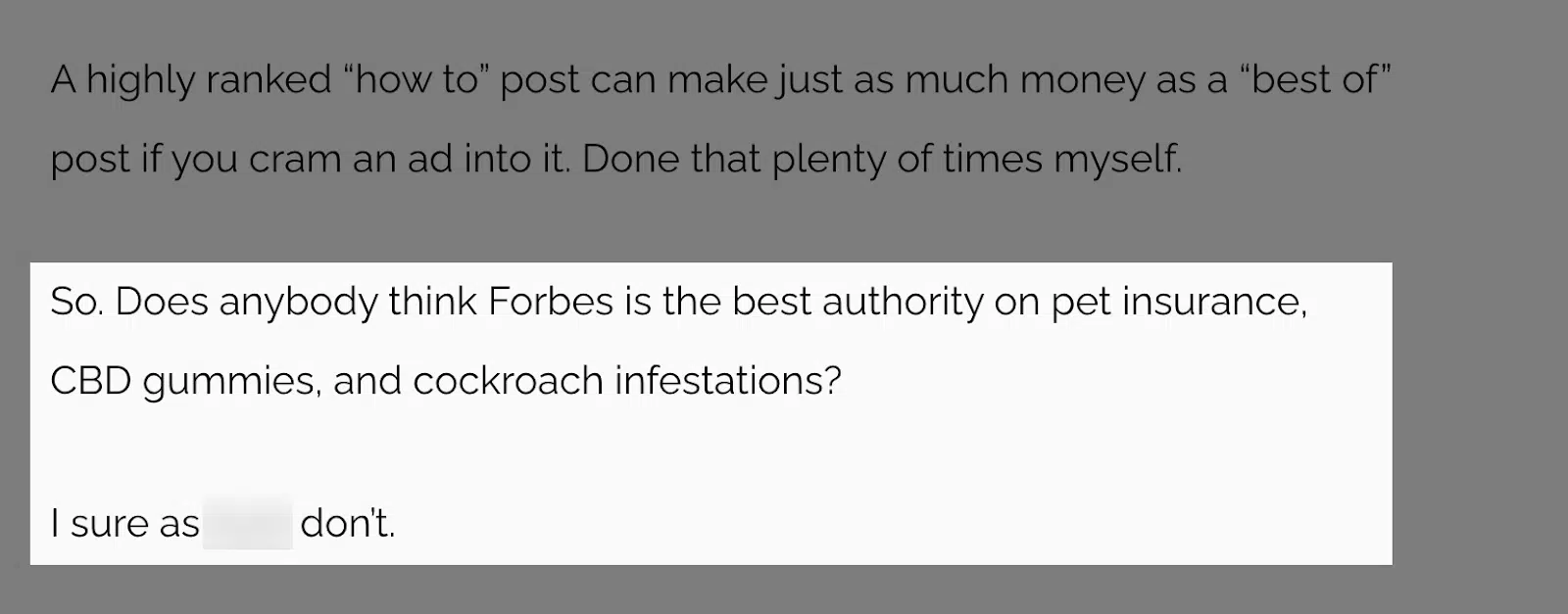

One of the most impactful SEO investigations this year was Lars Lofgren’s article, “Forbes Marketplace: The Parasite SEO Company Trying to Devour Its Host.”

The piece dives into Forbes Advisor’s parasite SEO program, developed in collaboration with Marketplace.co, and details the substantial traffic and revenue generated by the partnership.

Forbes Advisor alone was estimated to be making approximately $236 million annually from this strategy, according to Lofgren.

As Lofgren puts it:

This highlights the systemic problem with Google search.

Forbes Advisor is just one of the examples of parasite SEO programs that Lofgren investigates. If you want to go deeper, read his articles on other sites running similar programs.

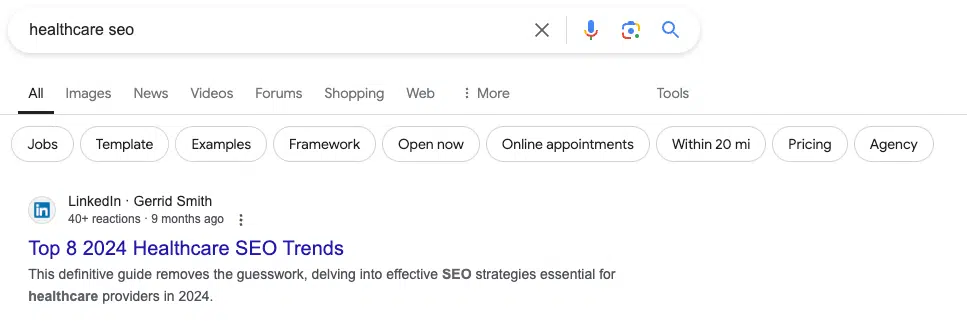

LinkedIn is another prime example. Over the past few years, users have increasingly leveraged LinkedIn’s UGC platform to capitalize on its powerful domain authority, pushing their content to the top of search results.

For instance, as of this writing, the top-ranking result for “healthcare SEO” is not from a specialized expert site but a LinkedIn Pulse article.

If you dig in their query data, you’ll see a range of queries from business, adult topics, personal loans and more.

Clearly, LinkedIn isn’t the best source for all of these things, right?

The rise of programs designed to manipulate search results has likely pushed Google to introduce the site reputation abuse policy.

The bigger problem

This brings me to why the policy isn’t enough. The core issue is that these sites should never rank in the first place.

Google’s algorithm simply isn’t strong enough to prevent this abuse consistently.

Instead, the policy acts as a fallback – something Google can use to address egregious cases after they’ve already caused damage.

This reactive approach turns into a never-ending game of whack-a-mole that’s nearly impossible to win.

Worse yet, Google can’t possibly catch every instance of this happening, especially on a smaller scale.

Time and again, I’ve seen large sites rank for topics outside their core business – simply because they’re, well, large sites.

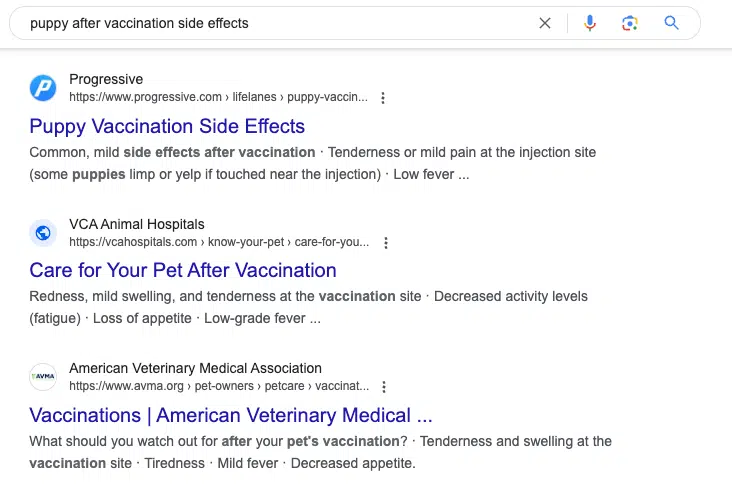

Here’s an example to illustrate my point. Progressive has a blog called Lifelines, which primarily covers topics related to its core business – insurance, driving tips, traffic laws, etc.

However, one of their blog posts ranks in Position 4 for the search query “puppy after vaccination side effects,” above actual experts like the American Veterinary Medical Association.

The result in Position 1? It’s Rover.com, a technology company that helps pet owners find sitters – still not a medical expert, yet leveraging its strong domain.

I’m not suggesting that Progressive is engaging in anything nefarious here. This is likely just a one-time, off-topic post.

However, the larger issue is that Progressive could easily turn its Lifelines blog into a parasite SEO program if it wanted to.

With minimal effort, it’s ranking for a medical query – an area where E-E-A-T is meant to make competition tougher.

The only way to stop this right now is for Google to spot it and enforce the site reputation abuse policy, but that could take years.

At best, the policy serves as a short-term fix and a warning to other sites attempting abuse.

However, it can’t address the broader problem of large, authoritative sites consistently outperforming true experts.

What’s going on with Google’s algorithms?

The site reputation abuse policy is a temporary band-aid for a much larger systemic issue plaguing Google.

Algorithmically, Google should be better equipped to rank true experts in a given field and filter out sites that aren’t topical authorities.

One of the biggest theories is the increased weight Google places on brand authority.

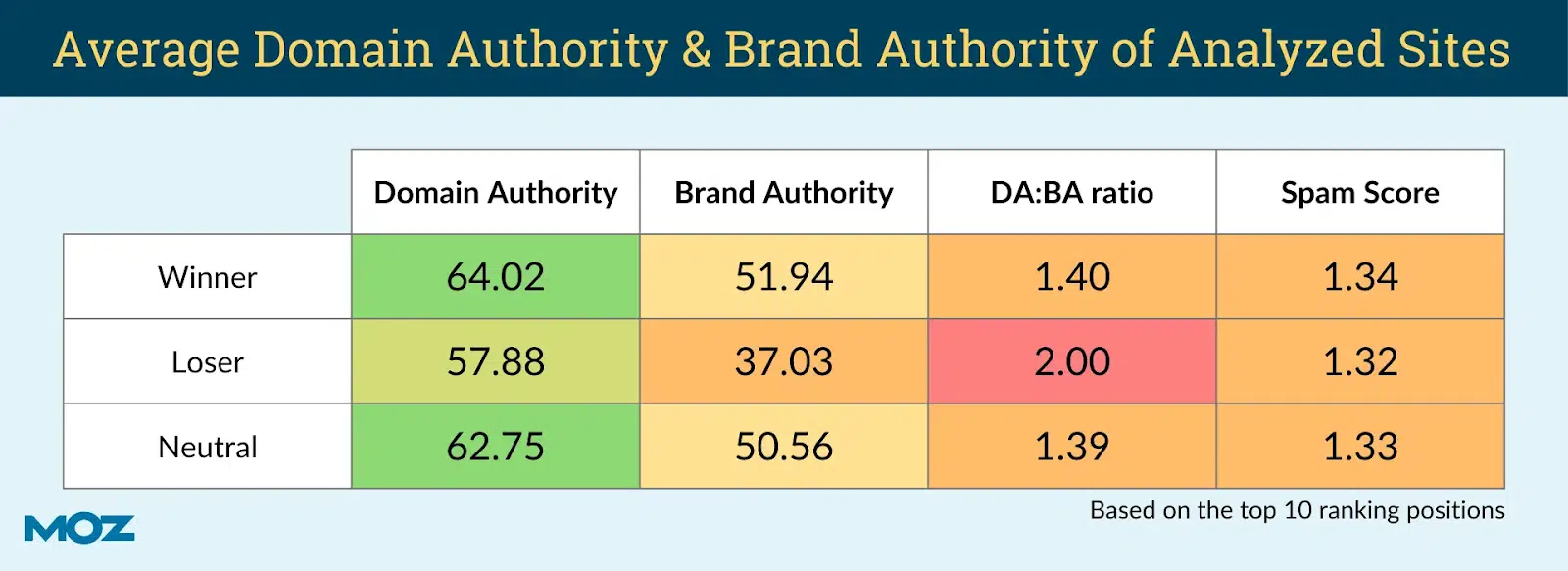

The winners of the helpful content update were more likely to have stronger “brand authority” than “domain authority,” according to a recent Moz study.

Essentially, the more brand searches a site receives, the more likely it is to emerge as a winner in recent updates.

This makes sense, as Google aims to rank major brands (e.g., “Nike” for “sneakers”) for their respective queries.

However, big brands like Forbes, CNN, Wall Street Journal and Progressive also receive a lot of brand search.

If Google places too much weight on this signal, it creates opportunities for large sites to either intentionally exploit or unintentionally benefit from the power of their domain or brand search.

This system doesn’t reward true expertise in a specific area.

Right now, the site reputation abuse policy is the only tool Google has to address these issues when their algorithm fails.

While there’s no easy fix, it seems logical to focus more on the topical authority aspect of their algorithm moving forward.

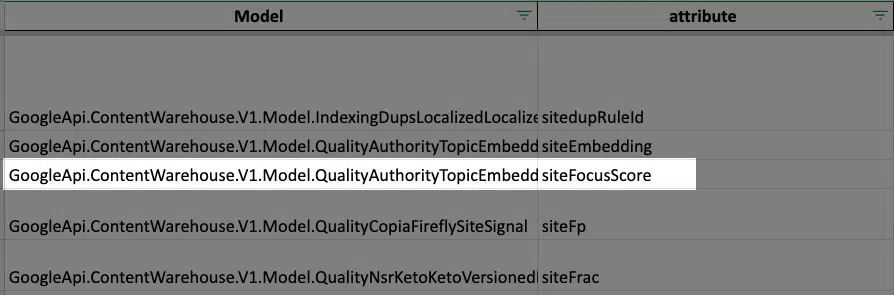

When we look at the Google Search API leaks, we can see that Google could use different variables to determine a site’s topical expertise.

For instance, the “siteEmbedding” variable implies they can categorize your whole site.

One that stands out to me is the “siteFocusScore” variable.

It’s a “number denoting how much a site is focused on one topic,” according to the leaks.

If sites begin to dilute their focus too much, could this be a trigger indicating something larger is at play?

Moving forward

I don’t think the site reputation abuse policy is a bad thing.

At the very least, it serves as a much-needed warning to the web, with the threat of significant consequences potentially deterring the most egregious abuses.

However, in the short term, it feels like Google is admitting that there’s no programmatic solution to the problem.

Since the issue can’t be detected algorithmically, it needs a way to threaten action when necessary.

That said, I’m optimistic that Google will figure this out in the long run and that search quality will improve in the years to come.

Contributing authors are invited to create content for Search Engine Land and are chosen for their expertise and contribution to the search community. Our contributors work under the oversight of the editorial staff and contributions are checked for quality and relevance to our readers. The opinions they express are their own.

Related stories