Overthrow The Tyranny Of Paid Search Budgets

Budgets are a fact of life for many paid search program managers. Budgets are essential for some firms, unnecessary but required nevertheless for others; and, on too many occasions, an onerous impediment to success in paid search. I’ve argued in the past that many in the e-commerce space should not budget search at all. If […]

Budgets are a fact of life for many paid search program managers. Budgets are essential for some firms, unnecessary but required nevertheless for others; and, on too many occasions, an onerous impediment to success in paid search.

Image via Shutterstock

I’ve argued in the past that many in the e-commerce space should not budget search at all. If ROI is positive, why constrict spend if you would be making money by spending more? If ROI turns negative, why keep spending? Revenue comes in before you pay the engines, so there isn’t even a cash flow constraint for many in the e-commerce sector.

However, budgets are necessary for some businesses including some in e-commerce. Seasonal inventory, style changeover, etc., might necessitate a fairly strict budget because you can’t sell more than you have. When success metrics are sales leads, video views, app downloads, etc., and actual revenue is far separated from the costs, budgeting is prudent.

Don’t Let Your Budget Become A Tyrant

As a brand-building vehicle, spend must make sense in the context of the whole media plan. Sometimes, it’s simply the nature of the company to budget either as a vehicle for planning or a mechanism for creating accountability.

The latter is how budgets can go from being useful tools to being debilitating tyrants.

Let’s look at this from an e-commerce perspective: try to imagine the following conversation happening in your business:

Paul Pennypincher: Sally, last month’s revenue was 20% above forecast.

Sally Salesmanager: Yes, we had a terrific month on the sales floor!

Paul Pennypincher: That’s a problem.

Sally Salesmanager: How is that a problem?

Paul Pennypincher: You went 20% over budget on sales commission.

Sally Salesmanager: Yes, but that’s a good thing, right?

Paul Pennypincher: Ha! How is overspending a good thing?

Sally Salesmanager: Ummm, it’s not like we hired extra staff, our sales folks just did a great job increasing close rates and average purchase prices. That’s what we want them to do, right?

Paul Pennypincher: Not if it means spending too much on commissions!

Sally Salesmanager: So, should I have told them to stay home for the last week, or to keep selling without getting paid commission?

Paul Pennypincher: Not my problem. Hit your numbers or hit the road…

Clearly, this argument is absurd and would never take place. But similar conversations happen in the context of paid search all the time.

Many companies have a section of expenses that roll into “cost of revenue.” These are expenses that rise and fall with sales. Expenses are like sales commissions, boxes and packing nuts, credit card fees, etc. They’re in the budget as a percentage of revenue. No one argues about those expenses; it’s understood that we want them to go up because they only go up when revenue does.

Managed well, paid search media (and often third-party management costs) can be treated in exactly the same way. The decision to treat the ad spend as a cost of revenue instead of part of the media budget is simply an accounting choice.

Provided you can hit your efficiency metrics routinely over time, this construct allows paid search managers to focus on one and only one thing: how can we efficiently drive more revenue to my company through paid search? Just as we don’t want salespeople looking back and forth at a mythical commission budget day to day, we don’t want our sales drivers in search doing that, either.

Too often, budgets become the focal point of a paid search manager’s attention. This happens to the detriment of the program in several different ways.

Time Spent Forecasting. I’ve done a lot of forecasting in my day, including catalog response rates, likely impacts of offers, required pick-face inventory levels, catalog requests, RKG business metrics of all sorts, paid search revenues and cost/benefit tradeoffs on behalf of clients. I’ve learned one lesson over and over and over: the accuracy of forecasts does not improve with the complexity of the model.

The forecasts I’ve done on the back of a napkin have often been more accurate that the ones I’ve spent dozens of hours on. Forecasts are useful tools, but forecasting/budgeting can too easily become a full time job, and one that ultimately doesn’t add much value to the real objective of the business.

We want to be able to plan on revenue and profitability so that we may staff, spend, and invest appropriately. These are important operationally. Getting budgets wrong by wide margins can have serious impacts on a business. However, the goal of most businesses isn’t to hit their budgets. The goal is to grow and ultimately to grow profits. Unfortunately, companies often lose sight of this distinction.

Opportunity Cost. Closely related to the above, scarce human resources — and human resources are always precious — means time spent building forecasts and explaining shortfalls and overages is time not spent driving business.

The activities that drive the program forward are sacrificed on the altar of reporting on why what happened last month, last week, or yesterday and trying to predict what will happen tomorrow, next week and next month. Daily budgets incur more opportunity cost than weekly, weekly more than monthly and monthly more than quarterly.

As is often the case, studying performance vs. expectation can be useful when done as a diagnostic and in an effort to better predict the future. Understanding what has caused a genuine decline or increase over forecasts is important and can identify opportunities for positive change, or give early warning signals of changes to the competitive landscape.

Jumping through these same hoops daily or weekly becomes a monumental time sink that usually involves trying to explain statistical noise rather than genuine gaps between performance and expectations.

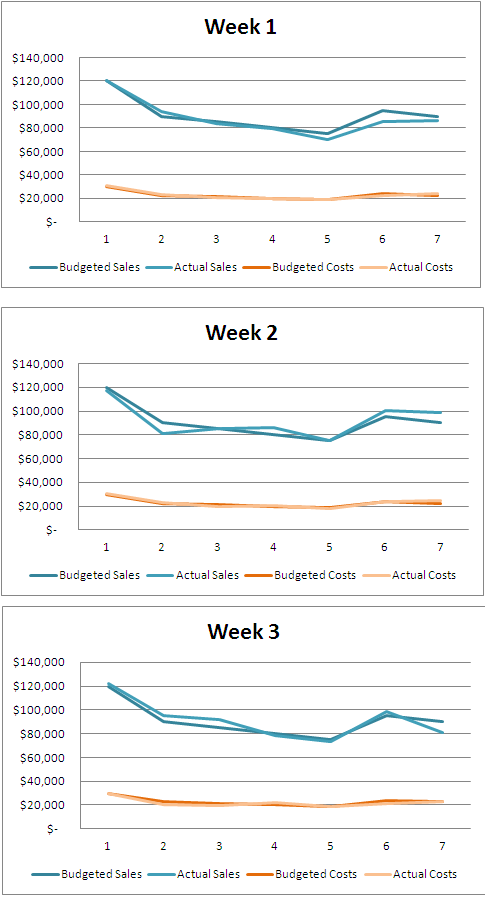

To make this case, I drew up a simple model. An advertiser wants a 4.0 ROI and has fixed daily budgets. Baking in a 10% variance (positive or negative) in both sales and spend — a very reasonable, conservative noise factor — against a spot on demand forecast results in the three different weeks looking like this:

Notice that the ROI variance from day to day is huge: 17% above one day; 12% below another. Weekly aggregates show week 1 is 4% below budgeted efficiency, and week 2 is 4% above. For the three week period as a whole, we’re 0.6% over efficient on 0.7% under spending and -0.1% of sales forecast.

Recall that this is a perfect forecast with just noise affecting the data! Failure to understand the effects of statistical noise can lead to hours and hours and hours of wasted analysis and reporting. Finding the right balance between ignoring budgets altogether — which is a good way to get fired — and wasting valuable time trying to explain noise is important.

Prediction Is Very Difficult

“Prediction is very difficult, particularly if it’s about the future.” — Niels Bohr

Evaluating the PPC team’s performance by how they stack up against the budget makes sense only if they developed the budget. It isn’t crazy to fault them, either, for not hitting an achievable forecast or badly mis-forecasting the opportunity, unless circumstances have changed dramatically with new competitors entering the field or major changes in competitor’s behavior, etc.

However, if instead, the budget is developed by folks who don’t understand the realities of the marketplace, the opportunity for budgets to be drawn to aspirations rather than realities makes it particularly foolish to gauge performance based on hitting goals.

Even if the PPC team did blow the projections, that should be one and only one piece of the evaluation of performance. The real performance evaluation should be tied to how well they managed against the opportunity, how well they use finite resources, and how well they use the available tools to fine tune the program and drive results.

Missing efficiency objectives cumulatively over a significant period of time is unpardonable. Failing to guess correctly what you can spend efficiently… not so much.

Positive, Tangible Harm

Constant measurement against budget has other immediate consequences beyond just the opportunity cost of time ill spent.

The ideal mechanism for spending a budget with maximum efficiency is portfolio optimization. The worst possible mechanism for spending a budget is tightening and loosening the engine campaign budgets.

Campaign budgets are a bad solution to budgeting by definition. When budgets come into play, the engines slow ad impression delivery to prevent over spending. That collection of keywords, therefore, generates fewer clicks than market demands, but your CPC remains unchanged.

By definition, if you hit the budget instead by reducing the bids to avoid overspending, you will get more traffic for the same overall cost. We know from our own research, Google’s research and the research of others in the space that by-and-large, the value of traffic does not change based on the position on the page; so, more clicks on the same ads mean more revenue. More revenue at the same ad spend is better ROI. Engaged engine budgeting mechanisms mean less than ideal ROI by definition.

Don’t Rely On The Engines To Manage Your Budget

In practice, they are even worse than this. To simplify the problem of hitting budgets and taking the ads out of the auction in the right amount, we have seen that the engines, in effect, stop serving the lower traffic tail and torso terms, serving instead primarily the higher traffic head terms as the data on likely traffic volumes are much richer and easier to predict.

Hence, we see the engines pausing what are often the highest converting keywords in the campaign in order to serve the lower converting, more general terms — a sure recipe for getting the least bang for your bucks.

I once made the analogy that engine budgets are like guardrails on a winding road: a useful safety feature, but a poor substitute for steering.

In theory, portfolio optimization works by analyzing the marginal return on investment for every ad in the account and bidding to achieve maximum ROI given a fixed budget. The all-knowing portfolio algorithm dials up the marginal ROI target to reduce spend, and dials down the marginal ROI target to increase spend to hit the desired budget. Done with perfect information about future search volume and demand elasticity, this guarantees getting the maximum return for a fixed investment amount.

In practice, data is imperfect and sparse. Pure portfolio systems have always struggled with the long tail as assumptions must be piled on top of assumptions. The complexity of the space, personalization of results, auction dynamics, traffic variations, sparse data and more make this a great theory that is all but impossible to implement effectively. Instead, we see portfolio systems forced to rely on the engine budgeting mechanism (campaign budgets, etc.) reaching in via API to raise and lower campaign budgets to hit the spend targets.

Ooooga. The “ideal” theoretical solution turns itself into the worst practical solution because there is no good way to ensure spending to a rigid budget otherwise.

Conclusion

Budgets can be both wise and necessary. However, whether budgets serve the needs of the company or become tyrants that dictate activities harmful to paid search success is a product of how they are used. Used as a planning tool and a means of establishing reasonable expectations, budgets can be helpful to the paid search team and to management. Used as the focus of performance evaluation and scrutinized daily, they can become barriers to success.

If you must budget, budget wisely. Don’t let poor use of MBO logic drive your team crazy and drive paid search performance downhill.

Contributing authors are invited to create content for Search Engine Land and are chosen for their expertise and contribution to the search community. Our contributors work under the oversight of the editorial staff and contributions are checked for quality and relevance to our readers. The opinions they express are their own.

Related stories

New on Search Engine Land