Feds Consider Google-ITA Deal: Damned If You Do, Damned If You Don’t

In what is becoming an annual ritual Google announces a dramatic acquisition, pundits speculate about the potentially market-changing impact and anti-trust investigators give it a long, hard look — only to allow it in the end. Last year the transaction in question was AdMob; this year it’s ITA software. Since the roughly $700 million deal […]

In what is becoming an annual ritual Google announces a dramatic acquisition, pundits speculate about the potentially market-changing impact and anti-trust investigators give it a long, hard look — only to allow it in the end. Last year the transaction in question was AdMob; this year it’s ITA software.

Since the roughly $700 million deal was announced in July federal regulators and anti-trust authorities have been seeking information from Google and talking to online travel companies. (The review is being conducted by the US Justice Dept. in ITA; it was the FTC in the case of AdMob.) Since ITA is the “infrastructure” behind many of the sites that Google would be competing with, although there are alternatives, the government wants to know how their fortunes would be affected. It also is trying to determine whether Google’s potential ability to send traffic to its own travel vertical might harm competitors.

The Wall Street Journal discusses the state of the inquiry:

Microsoft, Expedia and Kayak have expressed concerns to the Justice Department about the deal, arguing that combining the top Web-search company with the top airfare-search firm would give Google an unfair competitive advantage, people involved in the discussions said.

Other competitors have been more supportive. “Innovation in online travel has been stuck,” said Atanas Christov, chief executive of Vayant Travel Technologies LLC, which competes with ITA to provide search technology to airlines and travel websites . . .

From its stronghold in Web search—it handles more than 60% of Internet searches world-wide—Google has pushed into a wide range of other markets, such as selling mobile phones, developing broadband Internet, and online payments, sometimes through acquisitions of smaller firms.

So far, the company has been blocked by federal antitrust authorities only once — when it sought an advertising agreement with Web search rival Yahoo Inc. two years ago. But it faces closer scrutiny each time it buys a new company.

Both sides of the argument expressed in the excerpt are valid: the travel vertical has largely stagnated, although there are some who might argue otherwise. Google could bring some compelling new tools and services to market that would truly benefit consumers.

It’s also true that Google could direct users to its own services, which might quickly diminish the traffic and revenues that rivals could expect. The latter “risk” is quite real, not just because of Google’s ability to send traffic to itself but because “Google Travel” as a brand would instantly have more credibility than about 85 percent of travel sites out there.

As the WSJ article points out, Google won’t be selling tickets; however it will be selling ads against targeted traffic. But Google could quite easily best the user-experience on many travel sites and siphon off their traffic accordingly. A Google Travel would force competitors to build more compelling experiences and services, and move aggressively into social travel. From that standpoint it would spur innovation but some existing competitors would feel the sting almost immediately. I’m not going to handicap winners and losers right now but I have some in mind: those that do a version of arbitrage or offer lackluster user experiences.

The US government shouldn’t be in the business of protecting the revenues and market share of existing travel stakeholders and competitors. But it should recognize the powerful disruption that Google could cause to online travel. I’m sure there’s a compromise out there however.

My view in the AdMob case was that the government shouldn’t intervene (which in the end it didn’t thanks to Apple-iAd) because the market was too new, too quickly evolving and very competitive. This is a bit tougher in some respects.

If I were in the regulator’s chair I would probably permit the transaction but impose conditions on Google, requiring Google make ITA’s software available to existing customers and competitors for a period of years. The tougher part is placement in search results.

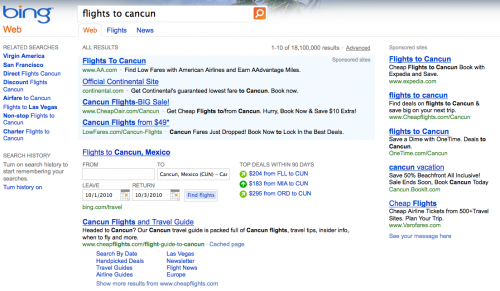

Microsoft bought Farecast, which became Bing Travel. And it shows up regularly at the top of Bing organic search results:

A strong comparable offering in Google results for travel queries would unquestionably capture some of the traffic going now to places like TripAdvisor, Orbitz, Kayak and Expedia. Those companies would effectively be compelled to advertise, which they do today, to overcome or combat the organic travel results that Google could put up. They could (and should) also build their brands and enhanced services to drive direct traffic.

It would be highly problematic, however, and a bad precedent for the government to set conditions surrounding where (on the page) and how Google could present travel results. Yet some Google critics want the government to do just that under a misguided theory of “search neutrality.”

There’s no simple answer: a Google Travel would certainly capture traffic but denying the transaction would amount to an official affirmation of the status quo and a vote against market competition in a different way.

Contributing authors are invited to create content for Search Engine Land and are chosen for their expertise and contribution to the search community. Our contributors work under the oversight of the editorial staff and contributions are checked for quality and relevance to our readers. The opinions they express are their own.

Related stories

New on Search Engine Land