When OCR Goes Bad: Google’s Ngram Viewer & The F-Word

Google launched its Google Books Ngram Viewer this week, a tool that lets you research how popular words and phrases have been over several centuries, based on their appearance in books. But can you trust it? In the case of the F-word, no — and perhaps in many other cases, as well. I read several […]

Google launched its Google Books Ngram Viewer this week, a tool that lets you research how popular words and phrases have been over several centuries, based on their appearance in books. But can you trust it? In the case of the F-word, no — and perhaps in many other cases, as well.

Google launched its Google Books Ngram Viewer this week, a tool that lets you research how popular words and phrases have been over several centuries, based on their appearance in books. But can you trust it? In the case of the F-word, no — and perhaps in many other cases, as well.

I read several mainstream news stories about the viewer after it launched, including a long piece in the Wall Street Journal. Those articles were generally filled with excitement. My own reaction to the tool was more muted. I immediately wondered if the underlying data was actually that accurate.

Counting Words Often Goes Wrong

For years, I’ve seen people try to use regular search data to plot the popularity of terms and trends over time. That’s been fraught with issues, in particular, when web pages have the wrong date on them. With the Ngram viewer, I figured it might have its own issues, such as:

- Does Google Books get the dates of some books wrong?

- Is the distribution adjusted? IE, if you have more books in a particular year, can that cause some terms to spike?

- Are the books “even” in subject matter? IE, do you have more scientific works scanned in one year than maybe another year?

Scanning Isn’t Perfect

I hadn’t thought of an even more basic problem: OCR errors. OCR stands for optical character recognition, the technology of scanning an image of a word and recognizing it digitally as that word. It’s how Google has “read” the 5 million books that the Ngram Viewer lets you search against.

OCR isn’t perfect. Sometimes words aren’t recognized correctly. Google’s Ngram Viewer FAQ page addresses this (and covers some other issues like those I’ve raised above, and how they’re adjusted for):

Why does the word “Internet” occur before 1950?

Most of those are OCR errors; we do a good job at filtering out books with low OCR quality scores, but some errors do slip through.

What A Difference An S Makes

That leads me to the F-word. For those who are sensitive, look away. I’ll be using the full word shortly, as it’s pretty awkward to write about this particular case without using it.

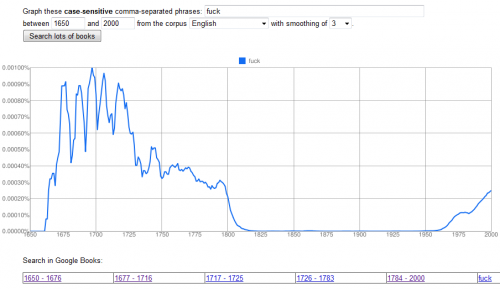

Yesterday, I saw venture capitalist Dave McClure mention a tweet from Brad Feld that linked to a chart of the word “fuck” being used from the 1600s through today. Curious, I took a deeper look. Here’s the chart:

You can see these huge spikes in usage early on the chart, but then by the 1800s, usage disappears until around 1960. What happened?

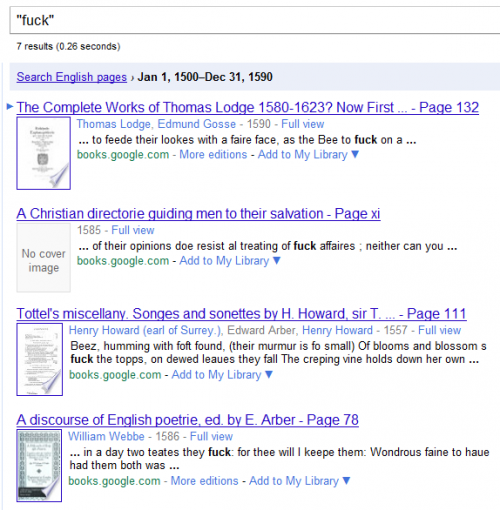

Well, at the bottom of the chart, you can see different years listed. Click on one of those year segments, and you get back a listing of books that contain the word, for that time period.

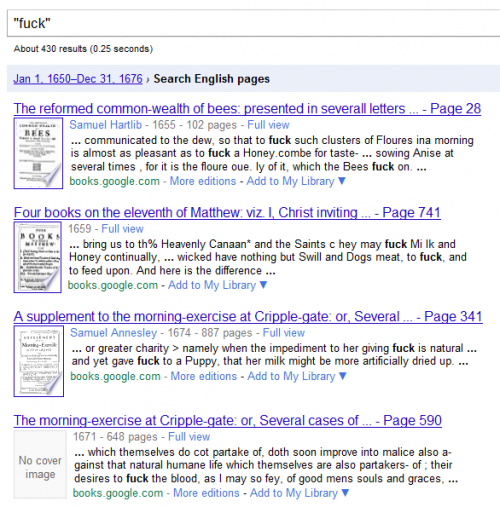

For the first period, 1650-1676, this is what I got:

You can see the mentions of “fuck” highlighted in bold. You can also see that they make little sense. From one:

their desires to fuck the blood

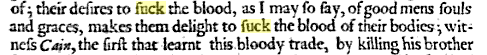

Fuck the blood? Was that supposed to be “suck the blood?” Yes, it was. The F in most of these cases — probably all of them — is in reality an S.

The Medial S

What happened? Blame the “medial s” (more about it here and here) That’s an archaic form of the letter S, where it looks similar to an F.

American students who puzzled over early government documents like The Bill Of Rights and seeing mentions of “Congrefs” are familiar with this (the image at the top of this article comes from an image of the Bill Of Rights from Wikipedia).

As a result, this usage of suck from the 1600s:

Is treated the same as the actual word “fuck” as written in 1991:

Google’s Ngram Viewer FAQ mentions this is a problem:

Why do I see so many misspellings like thif from pre-1800 Englifh books?

Use of the medial s.

To me, this seems like a big issue. S is a common word in the English language. If it’s not being distinguished from F, how accurate are all these charts being produced?

Not Found: First Written Usage Of “Fuck”

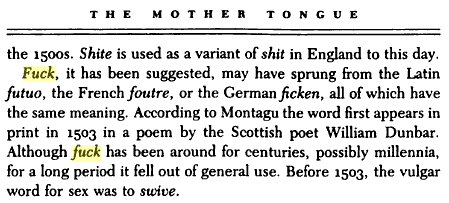

By the way, that 1991 reference about “fuck” is from Bill Bryson’s book, The Mother Tongue, where he explores the history of English. You can see in the screenshot from it above that Bryson writes that the first printed usage of the word “fuck” is in a poem by William Dunbar from 1503.

Google Books goes back that far, but ironically, it doesn’t find Dunbar’s poem with that word:

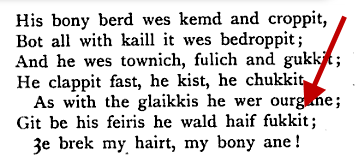

Instead, to locate it, I had to do some further research outside of Google Books, to locate the exact work attributed with the usage — “A Brash Of Wowing” — and discover that the exact spelling is “fukkit” rather than “fuck,” as you see here:

See the challenge? If you’re trying to track back to the first use of “fuck” (or any word) using the Ngram viewer, you’d better be checking for all forms of that word — and that means having a good knowledge of how language has changed, over time.

Further, the task is complicated by reprints. After several searches, I couldn’t find the original printing of “A Brash Of Wowing” from the 1500s (which doesn’t surprise me, as it has to be extremely rare). But I had no problem finding copies from later dates, such as 2003. Those reprints may skew the usage of words higher, potentially, over time.

Searcher, Beware

I’m hoping that the academic researchers using this material are indeed adjusting for these and other potential traps. It would be terrible if they’re simply taking whatever numbers the Ngram viewer spits out without doing some deep analysis in each case they study.

For the casual searcher, the Ngram viewer needs to be taken with a huge grain of salt, I’d say. It’s fun. It might give you some idea of trends. But it could also be putting out data that’s all fukkit up.

Postscript: Gary Price of ResourceShelf pointed out this post from the Binder Blog that takes another look at problems with the Ngram viewer.

Contributing authors are invited to create content for Search Engine Land and are chosen for their expertise and contribution to the search community. Our contributors work under the oversight of the editorial staff and contributions are checked for quality and relevance to our readers. The opinions they express are their own.

Related stories

New on Search Engine Land