How Google is tackling fake news, and why it should not do it alone

What can Google do to combat fake news? Columnist Ian Bowden illustrates some ways the search giant can tackle -- and already is tackling -- this problem.

Fact-checking and preventing fake news from appearing in search results will remain a big priority for search engines in 2017.

Following the US election and Brexit, increased focus is being placed on how social networks and search engines can avoid showing “fake news” to users. However, this is a battle that search engines cannot — and more fundamentally, should not — fight alone.

With search engines providing a key way people consume information, it is obviously problematic if they can both decide what the truth is and label content as the truth. This power might not be abused now, but there is no guarantee of the safe governance of such organizations in the future.

Here are five key ways Google can deal (or already is dealing) with fake news right now. They are:

- Manually reviewing websites

- Algorithmically demoting fake news

- Removing incentives to create fake news

- Signaling when content has been fact-checked

- Funding fact-checking organizations

1. Manually reviewing websites

Google does have the power to determine who does and does not appear in their various listings. To appear in Google News, publishers must meet Google’s guidelines, then apply for inclusion and submit to a manual review. This is not the case with the content that appears in traditional organic listings.

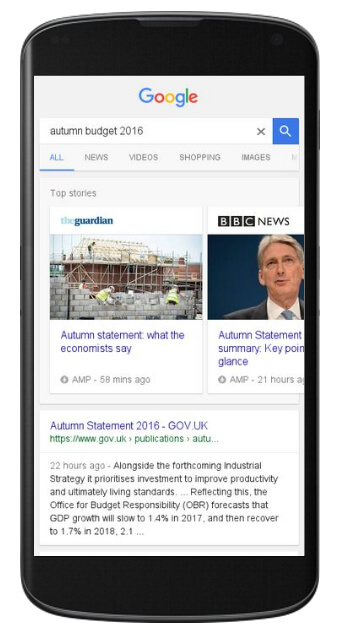

Understanding how each part of the search results is populated, and the requirements for inclusion, can be confusing. It’s a common misconception that the content within the “In the news” box is Google News content. It’s not. It may include content from Google News, but after a change in 2014, this box can pull in content from traditional search listings as well.

“In the news” appears at the top of the page for certain queries and includes stories that have been approved for inclusion in Google News (shown above) as well as other, non-vetted stories from across the web.

That’s why Google was criticized last week for showing a fake news story that reported a popular vote win for Trump. The fake story appeared in the “In the news” box, despite not being Google News (so it was not manually reviewed).

There needs to be better transparency about what content constitutes Google News results and what doesn’t. Labeling something as “news” may give it increased credibility for users, when in reality it hasn’t undergone any manual review.

Google will likely avoid changing the carousel to a pure Google News product, as this may create concerns with news outlets that Google is monetizing the traffic they believe is being “stolen” from them. Unless Google removes any ads appearing against organic listings when a news universal result appears, Google has to make this carousel an aggregation of the net.

It hasn’t been confirmed yet at time of writing, but there is speculation that Google is planning to reduce the ambiguity of the “In the news” listings by replacing it with “Top stories” (as seen in its mobile search results). Like content from the “In the news” box, these listings have been a mashup of Google News and normal search listings, with the common trait being that these pages are AMP-enabled.

“Top stories” consists of AMP web pages.

In my opinion, “Top stories” still implies an element of curation, so perhaps something like “Popular stories from across the web” may work better.

Manual review isn’t viable for the entire web, but it’s a start that items from Google News publishers are manually reviewed before inclusion. The opportunity here is to be more transparent about where content has been reviewed and where it hasn’t.

2. Algorithmically demoting fake news

Traditionally, search engines have indirectly dealt with fake news through showing users the most authoritative search results. The assumption is that domains with higher authority and trust will be less likely to report fake news.

It’s another debate whether “authority” publications actually report on the truth, of course. But the majority of their content is truthful, and this helps to ensure fake news is less likely to appear in search results.

The problem is, the very ranking signals search engines use to determine authority can elevate fake news sites when their content goes viral and becomes popular. That is why, in the above example, the fake news performed well in search results.

Google’s ability to algorithmically determine “facts” has been called into doubt. Last week, Danny Sullivan on Marketing Land gave several case studies where Google gets it wrong (sometimes comically) and outlines some of the challenges of algorithmically determining the truth based on the internet.

Google has denied that TrustRank exists, but perhaps we’ll see the introduction of a “TruthRank.” There will be a series of “truth beacons,” in the same way the TrustRank patent outlines. A score could be appended based on the number of citations against truth-checking services.

3. Removing the incentive to create fake news

There are two main goals for creating fake news websites: money and influence. Google not only needs to prevent this material from appearing in search results but also needs to play a role in restricting the financial incentive to do it in the first place.

Google AdSense is one of the largest ad networks, and it was one of the largest sources of income for authors creating fake news. One author of fake news around the US election was reportedly making $10,000 per month.

Earlier this month, both Facebook and Google banned fake news sites from utilizing their ad networks. This is a massive step forward and one that should make a big difference. There are other ad networks, but they will have smaller inventory and should receive pressure to follow suit.

A Google spokesperson said:

“Moving forward, we will restrict ad serving on pages that misrepresent, misstate, or conceal information about the publisher, the publisher’s content or the primary purpose of the web property.”

Google can do little to reduce the incentive to create fake news for the purpose of political influence. If the effectiveness of producing fake news is reduced, and it culturally becomes unacceptable, it is less likely it would be used by political organizations and individuals.

4. Signaling when content has been fact-checked

In October, Google introduced a “Fact Check” label for stories in Google News, their objective being “to shine a light on [the fact-checking community’s] efforts to divine fact from fiction, wisdom from spin.” The label now appears alongside previously existing labels such as “opinion,” “local source” and “highly cited.”

Fact-checking sites that meet Google’s criteria can apply to have their services be included, and publishers can reference sources using the Claim Review Schema.

The kind of populism politics that has surfaced in both America and the UK is cynical of the establishment, and this cynicism could very easily extend to any fact-checking organization(s).

Trump has claimed the media is biased, specifically calling out sources such as The New York Times and The Washington Post. Any attack from influential people on the fact-checking organizations could quickly undermine their credibility in the eyes of populists. It needs to be communicated clearly that the facts are not defined by Google and that they are from neutral, objective sources.

Google has introduced a new “Fact Check” label.

These labels only apply to Google News, but it will be interesting to see if and how Google can expand it to the main index.

5. Funding fact-checking organizations

Of course, Google should not be defining what the truth is. Having the power to both define veracity and present it back to society concentrates power that could be abused in the future.

Google, therefore, has a large dependency on other organizations to do this task — and a large interest in seeing it happen. The smart thing Google has done is to fund such organizations, and this month it has given €150,000 to three UK organizations working on fact-checking projects (plus others elsewhere in the world).

One of the UK organizations is Full Fact. Full Fact is working on the first fully automated fact-checking tool, which will lend scalability to the efforts of journalists and media companies.

Full Fact caps the amount of donations they can receive from any one organization to 15 percent to avoid commercial interests and preserve objectivity. This is the counter-argument to any cynics suggesting Google’s donation isn’t large enough and doesn’t represent the size of the task.

Google needs accurate sources of information to present back to users, and funding fact-checking organizations will accelerate progress.

To wrap up

Casting aside all of the challenges Google faces, there are deep-rooted issues in defining what constitutes the truth, the parameters of truth that are acceptable and the governance of representing it back to society.

For Google to appear to be objective in their representation of truth, they need to avoid getting involved in defining it. They have a massive interest in this, though, and that’s the reason they have invested money into various fact-checking services.

Over the past decade, it’s possible to point to where the main focus of search engines has been, e.g., content or links. Going forward, I think we will see fact-checking and the tackling of fake news as high a priority as any other.

Google needs to act as a conduit between the user and the truth — and not define it.

Contributing authors are invited to create content for Search Engine Land and are chosen for their expertise and contribution to the search community. Our contributors work under the oversight of the editorial staff and contributions are checked for quality and relevance to our readers. The opinions they express are their own.

Related stories