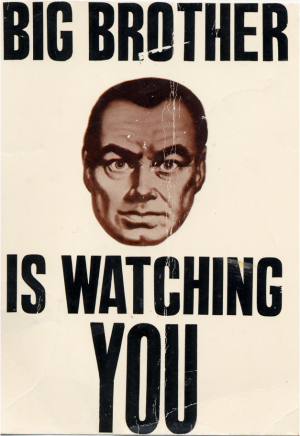

It’s Not About Cookies: Privacy Debate Happening At Wrong Level

Some form of digital privacy regulation in the US is about 90 percent certain in the coming year. In Europe, where privacy rules are much more stringent, the details of new consumer protections are currently being worked out on a practical level. For example on Wednesday the EU data protection authority decided that location data […]

Some form of digital privacy regulation in the US is about 90 percent certain in the coming year. In Europe, where privacy rules are much more stringent, the details of new consumer protections are currently being worked out on a practical level.

Some form of digital privacy regulation in the US is about 90 percent certain in the coming year. In Europe, where privacy rules are much more stringent, the details of new consumer protections are currently being worked out on a practical level.

For example on Wednesday the EU data protection authority decided that location data will be classified as personal information. What that will mean is that location data collection in Europe will become opt-in rather than opt-out. As you already know Europe is also putting lots of rules around cookies (and in some cases analytics).

Focus on What Matters

Much of the privacy debate has focused on cookies and icons and not what really matters: the misuse or abuse of consumer data by third parties in the real world. I don’t care whether I see behaviorally targeted ads so much as I don’t want my health care or auto insurance to be impacted by sites I’ve visited and stuff I post online.

That’s what matters in a practical sense. And by refocusing the discussion on the real-world consequences of profiling I believe the industry and regulators could come to a meeting of the minds more swiftly.

(In China it’s a different story; the stakes are much higher and the consequences of tracking more dire.)

“Privacy Not the Enemy of Innovation”

Yesterday the US Senate Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation held a privacy hearing that focused on tracking and protection of children, with an emphasis on mobile tracking and geolocation. Each of the formal company statements (from Google, Facebook, Apple) can be found here. And each of the companies testifying expressed broad support for privacy and said they were protecting consumers in various ways.

Several members of the committee warned of “unintended consequences” and the potential economic harm of privacy regulation. However Senator John Kerry and other members of the subcommittee expressed support for “innovation” but also rejected the idea that industry self-regulation would create sufficient protection for consumers. Kerry added, “I reject the notion that privacy protection is the enemy of innovation.”

Kerry has introduced the “Consumer Privacy Bill of Rights” and fellow Democrat Jay Rockefeller introduced “Do Not Track” legislation. Kerry repeatedly stated that consumers should be told what data are being collected, how they’re being used and by whom. Here’s an excerpt from Rockefeller’s prepared remarks:

As smartphones become more powerful, more personal information is being concentrated in one place. . . The mobile marketplace is so new and technology is moving so quickly that many consumers do not understand the privacy implications of their actions.

[C]onsumers want to understand and have control of their personal information. According to a survey commissioned by the privacy certification company TRUSTe, 98 percent of consumers express a strong desire for better controls over how their personal information is collected and used by mobile devices and apps. Unfortunately, today this expectation is not being met . . .

Finally, I believe consumers deserve a simple, easy-to-use process to stop companies from collecting personal information. Last week, I introduced the Do-Not-Track Online Act of 2011, which directs the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) to establish standards by which consumers can tell online companies, including mobile applications, that they do not want their information collected. The FTC would then make sure companies respect that choice.

Committee Told Sites Not Doing Enough for Consumers

Amy Guggenheim Shenkan, President and COO of Common Sense Media, told the committee that the companies testifying weren’t doing enough to protect children and privacy and that they should devote more resources to those objectives. Facebook’s Bret Taylor was grilled by committee chair Rockefeller about the millions of underage kids who have Facebook accounts. While Taylor was sincere and said “all the right things,” he was met with skepticism by Rockefeller.

On the same day as the hearings, the Wall Street Journal reported that social widgets (e.g., the Facebook Like button) track data about users and their path through the internet without disclosing any of that activity:

The widgets, which were created to make it easy to share content with friends and to help websites attract visitors, are a potentially powerful way to track Internet users. They could link users’ browsing habits to their social-networking profile, which often contains their name.

For example, Facebook or Twitter know when one of their members reads an article about filing for bankruptcy on MSNBC.com or goes to a blog about depression called Fighting the Darkness, even if the user doesn’t click the “Like” or “Tweet” buttons on those sites.

For this to work, a person only needs to have logged into Facebook or Twitter once in the past month. The sites will continue to collect browsing data, even if the person closes their browser or turns off their computers, until that person explicitly logs out of their Facebook or Twitter accounts, the study found.

Facebook, Twitter, Google and other widget-makers say they don’t use browsing data generated by the widgets to track users; Facebook says it only uses the data for advertising purposes when a user clicks on a widget to share content with friends.

Disclosures Aplenty

This is precisely the kind of practice that in the future will need to be disclosed, together with an opt out capability. The difficult question is how can, for example, the benefits of Facebook Connect be preserved while simultaneously informing consumers in simple language about what’s happening with their data without scaring them?

Some have suggested coming disclosure rules will mean a deluge of pop-ups. That would be very undesirable for everyone: publishers, advertisers and users alike.

The not-unfounded fear of many publishers and ad networks is that disclosures will lead to lots of consumers opting out. For example, if there were a way to turn off ad-targeting on Facebook most people would probably do it. (Search advertising is largely exempt from the debate because by nature it’s opt-in.)

But people also want free services and generally would rather see “relevant” ads than low-quality generic ads that have absolutely nothing to do with them. The online advertising industry has done a dismal job of educating consumers about some of the benefits of targeted ads and how they subsidize free content online. Part of that is attributable to arrogance and paternalism: what consumers don’t know won’t hurt them.

That attitude will no longer work however.

Stopping Insurance Companies from Abusing Using Online Data

As suggested above, one potential way to reconcile the objectives of the privacy advocates and online marketers is to go after the real-world impact of profiling and prevent misuse of consumer data by third parties such as divorce lawyers, insurance companies, mortgage banks, potential employers and the police. That should be the real target of consumer privacy rules (although the mechanics of implementing and enforcing this approach are challenging). Giving consumers confidence that data collected about their online behavior “won’t fall into the wrong hands” or be “used against them” is what we should really be after.

Talking to consumers about the nuances and operation of cookies and online data collection is not only challenging most consumers aren’t interested. Nobody reads terms of service agreements, for example, they just click “accept.”

While consumers should be told who gets access to their data, nobody wants their online experience to be characterized by pop-ups at every turn or confronted by lawyer-drafted gibberish each time they visit a site. What people really want is assurances that insurance carriers won’t deny coverage or banks deny loans based on online data mining.

This is the level at which the debate should be happening. Then the “tactics” or the mechanics of privacy become somewhat easier to work out.

(Photo courtesy Mark Evans. Used with permission.)

Contributing authors are invited to create content for Search Engine Land and are chosen for their expertise and contribution to the search community. Our contributors work under the oversight of the editorial staff and contributions are checked for quality and relevance to our readers. The opinions they express are their own.

Related stories