Organic Search & Paid Search: Are They Synergistic Or Cannibalistic?

One aspect to search marketing that I feel doesn’t get enough attention and indeed is misunderstood by the SEO practitioner is the interaction between organic search and paid search. For years when teaching SEO workshops, I touted the synergistic effect of being at the top of both organic and paid results. I would encourage attendees […]

One aspect to search marketing that I feel doesn’t get enough attention and indeed is misunderstood by the SEO practitioner is the interaction between organic search and paid search.

For years when teaching SEO workshops, I touted the synergistic effect of being at the top of both organic and paid results. I would encourage attendees to invest in both SEO and PPC on the promise of symbiosis between the two marketing channels. I would cite research showing that you can increase the clickthrough rate of your #1 (organic) ranking if you also have a sponsored ad above it or in the right column, and that showing up twice on the same page in the results makes your #1 ranking get 20% more clicks.

I gave short shrift to the thought that engaging in both sides of search marketing could lead to an adverse effect, i.e. negative synergy — whereby your paid search program cannibalizes your organic search derived visits, or vice versa. That is, until just a couple weeks ago.

What shifted my thinking was a session at the recent Silicon Valley Search Engine Roundtable’s “Rockstar” conference (ironically named, given the “Covariopalooza” rock-themed customer conference that Covario put on earlier in the week!) Also ironic was the fact there was a presentation given by one of my company’s own “rock stars”, namely our Chief Analytics Officer Dr. Matthias Blume. The premise of the talk was how the organic and paid results interact and how flawed attribution modeling can misrepresent ROI, associating sales/conversions with the wrong marketing program (i.e. SEO when PPC should have gotten the credit, PPC when SEO should have gotten the credit).

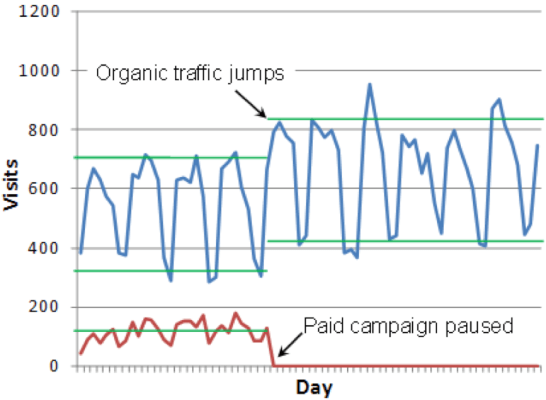

The cannibalization of organic search by PPC is clearly demonstrated by the following (inadvertent) experiment where paid search was shut off completely for a time. As evidenced by the graph below, there’s an increase in organic traffic commensurate with the decrease in PPC derived traffic. (Note that measurement of this effect is confounded by other factors such as cyclical patterns, other marketing actions taken by both you and your competitors, the economy, the weather, and so on.)

How does this sort of thing happen? Consider a multi-touch situation where a first-time visitor enters via an organic listing but leaves without buying anything; the visitor returns days later via a paid listing, this time making a purchase. If your organization assigns 100% of the value of that transaction to the last click, then the paid listing gets the credit when in fact the organic listing did most of the heavy lifting. Conversely, if your organization’s policy is to recognize the first click, organic gets too much credit.

Consider also the opposite scenario where the paid click is the visitor’s first point of entry. Then later an organic click is what leads to the purchase. “Last click” would overstate the value attributable to SEO, “first click” would overstate the value attributable to PPC.

The best option would be to assign a portion of the value across all touchpoints, with greater emphasis on the first click.

The ROI of PPC is further exaggerated by the fact that URLs in paid ads are invariably tagged with tracking parameters, whereas organic listings are not. This is regardless of where in the buying cycle the user interacts with the paid listings. That’s because analytics packages tend to favor tracking parameters over the referrer (which is passed in the HTTP header) as an indicator of the lead source. Tracking parameters in organic URLs are, as you may already know, considered bad SEO practice: they lead to duplicate content and PageRank dilution.

Consequently, the SEO must rely on the referrer string to supply the visitor’s point of origin, despite the fact that it is the inferior measure. (Inferior for many reasons, not the least of which is the fact that privacy/security tools installed on the user’s PC such as Norton Internet Security wipe the referring URL from user’s requests yet thankfully leave tracking parameters intact.)

These attribution inaccuracies obscure what’s really going on: the paid listing is cannibalizing the organic listing, i.e. drawing searchers away from the organic listing which would have otherwise been clicked on. This can happen, for instance, when you have a particularly effective paid ad creative, e.g. that calls out in the ad copy that it’s the “Official Site.”

Matthias also made the point that there’s a greater degree of cannibalization (negative synergy) when there is a combination of the following: a high organic ranking, a strong brand, and when the paid and organic listings are similar to one another but differentiated from competitors. But by the same token, the cost per click is the lowest for search terms that fit those criteria. Matthias’ advice to the PPC specialist (and this is particularly applicable if those who are budget-limited): reallocate your paid search spend to maximize true ROI.

If your SEO work is stealing clicks away from your paid counterpart, you may be inclined to think that is a good thing. It will, after all, save on some click charges. Actually, it’s a wash. As alluded to in the previous paragraph, Google will make up the lost revenue by charging a higher cost per click as a consequence of a lower clickthrough rate and thus a lower Quality Score. So in the end, Google still makes its money.

Given all this, what actions should you, the SEO practitioner, take?

For one, get a better handle on the true ROI of organic search, at the keyword level. That requires computing the synergy. How? You could pause your ads on certain queries and then analyze the resulting plots akin to the one above. Or use Covario’s paid/organic synergy score (POSS) methodology. In this case, you ask your PPC counterpart to reduce his/her actual CPCs on keywords with high organic conversion and high paid cost by 60% — no need to pause the ads. In the process, by looking at conversion and synergy at the search query level, the PPC advertiser will also hone in on the most effective terms through better use of negative keywords and greater use of exact match.

Then use 1+synergy as a multiplier on the value as determined by click-based attribution. ROI = ((1+POSS)*value – cost) / cost. This doesn’t go as far as Covario’s “True Value of Display” methodology, but it’s vastly better than ignoring paid/organic interaction. In our research we measured synergy from -95% to +25%. That’s quite a range. Obviously you’ll want to favor ads with positive synergy over those with negative synergy (all else being equal).

Another set of dials you can turn is what is displayed in your paid search ad. Test calls-to-action, mentioning specific product features, branding, “official site”, etc. and measure the impact on synergy.

The ultimate goal should be optimizing your ad creative and rebalancing your company’s paid search spend based on the true, adjusted ROAS where synergy is taken into account.

Contributing authors are invited to create content for Search Engine Land and are chosen for their expertise and contribution to the search community. Our contributors work under the oversight of the editorial staff and contributions are checked for quality and relevance to our readers. The opinions they express are their own.

Related stories

New on Search Engine Land