Privacy group files flawed complaint against Google Store Sales Measurement

EPIC gets the basic facts wrong about the data being used in Google program.

At a time when companies have growing access to consumer data from an increasing number of sources, privacy is more important than ever. But it’s also important for privacy advocates to understand what’s going on before they formally complain to regulatory bodies.

The Electronic Privacy Information Center (EPIC) has filed a complaint with the FTC over Google’s Store Sales Measurement program. The group is arguing that:

Google has collected billions of credit card transactions, containing personal customer information, from credit card companies, data brokers, and others and has linked those records with the activities of Internet users, including product searches and location searches. This data reveals sensitive information about consumer purchases, health, and private lives.

It asserts that Google is using a “secret, proprietary algorithm for assurances of consumer privacy” and that the company uses “an opaque and misleading ‘opt-out’ mechanism.” It further argues that these are “unfair and deceptive trade practices” and confer FTC jurisdiction. It’s asking for an injunction against these practices accordingly.

Store Sales Measurement began testing in 2014 and was rolled out in the US earlier this year. In contrast to the statement in the EPIC complaint, Google does not receive or have access to personal credit card transaction data.

What Google is getting is anonymous, aggregated information from credit card companies; it doesn’t see specific purchases and can’t identify individuals. Google also doesn’t know what was purchased; it receives information that among X number of users exposed to a digital ad campaign, a subset of that audience bought something in the advertiser’s store. That information (on an aggregate basis) is reported back to the advertiser to assess the efficacy of the campaign.

In addition, the data is encrypted and, according to Google, it cannot be used to identify individuals. Google told me through a spokesperson that it “does not share any personally identifiable information with advertisers or partners for this product.”

Google is not unique in this arena — Facebook introduced offline sales measurement through Custom Audiences in 2013. Other companies, such as Oracle and 4Info can do similar kinds of sales-related offline tracking.

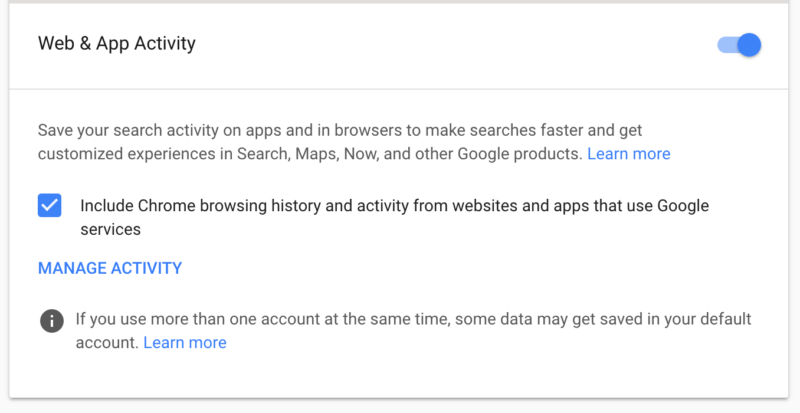

Google’s opt-out process is a available under Google My Activity–>Activity Controls. Users can opt-out by unchecking the box below.

Google has not done a good job publicizing this opt-out option, nor is it intuitive. Clearly that process can be dramatically improved.

EPIC is right to push for more transparency around privacy and use of consumer data. However in this case they get some basic facts wrong.

By the same token, Google, Facebook and others can do a better job educating consumers about how their data is being used and the kinds of controls that can be exercised over that data. Both companies over the past couple of years have tried to do this with mixed results.

Most consumers don’t really have a clear sense of how their digital data is being used behind the scenes. But in the case of Google’s Store Sales Measurement, it’s not being misused.

Postscript: The Future of Privacy Forum‘s founder Jules Polonetsky provided the following comment on this matter in response to an email request from me:

It’s no surprise that reports using credit card data are controversial, but it’s commendable that Google has managed to do this by using homomorphic encryption, where reports can be run on data that is fully encrypted and no personal data needs to be shared. If this technology can be advanced, it is a step towards the holy grail of being able to gain insights from data sets with sharing personal information. When the dust clears, privacy researchers will likely see great value in the privacy enhancing technology used here.

Contributing authors are invited to create content for Search Engine Land and are chosen for their expertise and contribution to the search community. Our contributors work under the oversight of the editorial staff and contributions are checked for quality and relevance to our readers. The opinions they express are their own.

Related stories

New on Search Engine Land