“Search” Beyond The “Engine”: Alternative Search Sites

By now, you’ve all heard about this new whatchamacallit – the Googles. We all use the Googles quite a bit in our daily routines, and some of us even do a bit of marketing on them, too. However, as search evolves and continues to be fused with display, it’s important for marketers to take a […]

By now, you’ve all heard about this new whatchamacallit – the Googles. We all use the Googles quite a bit in our daily routines, and some of us even do a bit of marketing on them, too.

However, as search evolves and continues to be fused with display, it’s important for marketers to take a step back and consider how and why consumers use conventional search engines, what type of data is afforded from these search engines and what types of results marketers want to gain.

Why Do Consumers Use Search Engines?

Most people use Google, Yahoo! or Bing to initiate the purchase cycle when seeking a product to buy.

The goal at this point of the consideration process is to decide whether or not they’re interested in a product at all. Think of the moment (hopefully years ago) that you finally decided to replace your Blackberry (sorry, RIM) with an iPhone or an Android.

Note: If you haven’t yet switched, then this means you’re currently performing the search example I’ve illustrated below. Or, you should be.

Say you visited one of the larger search engines like Google and searched “iPhone vs. Android” or “smartphone comparison.” You weren’t planning on purchasing a replacement on the spot, but rather, you wanted to research both types of smartphones with the plan of eventually narrowing down your choice to just one of the two.

The goal of your search was to begin the product consideration process and decide if you wanted a replacement for your Blackberry (in this example, the “Blackberry replacement” itself is the product).

2. People use search engines to find the exact product they want to purchase.

After you’ve performed the above search, you likely won’t come back to search on Google, Yahoo! or Bing until you’ve decided on the exact product that you want.

Something important happened between the first round of “iPhone vs. Android” searches and your final search, “Verizon iPhone 4S NYC sale” – but we’ll get to that in a moment.

The point is that once you’ve made up your mind, you are less likely to navigate Verizon’s website. You want Google to do the work for you, so you type in a super-descriptive search as a way of saying “Hey, Google, the least you can do is save me some time by navigating me to the product page.”

Google obliges by providing you with the exact result that you were seeking, and you then go on to purchase your shiny new addiction.

To summarize the above example: you used Google to confirm that you wanted to replace your Blackberry, and then you circled back to Google when you were ready to pull the trigger on a purchase.

But What Happened In Between?

If you’re like most consumers, you did quite a bit of research in between your first wave of Google searches and your final “purchase search” on Google.

Earlier this year, PwC surveyed consumers’ online behaviors and released a report showing that nearly 88% of consumers conducted research online before purchasing a product.

In the Blackberry replacement scenario, consumers most likely conducted their research on vertical sites with product reviews and shopping comparison engines, such as CNET, Engadget or even eBay.

The time during which consumers gather information about a product that they are interested in represents the optimal time for brands to influence customer brand preference and purchasing decisions. Consumers want to research product features, user reviews and average prices.

Throughout this process, how did those consumers conduct their online navigation? Through search! However, they did not search on search engines; instead, they were searching within alternative search properties that have a search box within their site.

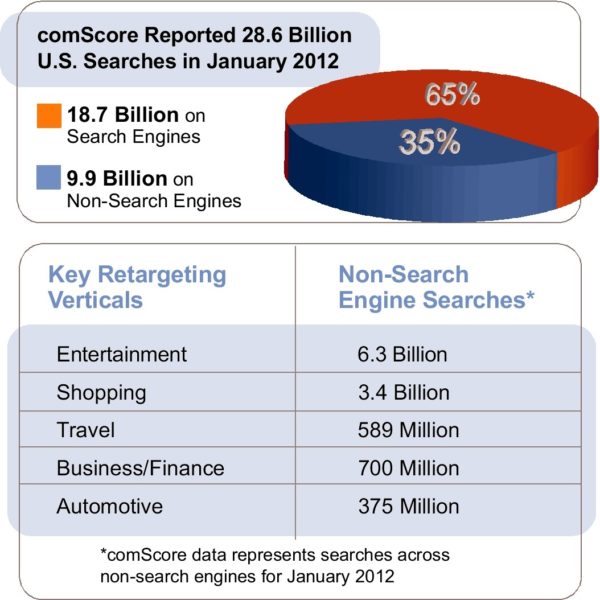

According to comScore data, approximately 62 million U.S. searches will take place on search engines on an average day – and more than 33 million will take place on alternative search sites. These numbers indicate a lot of search activity happening beyond search engines.

What Does This Mean For Marketers?

Users begin and end their purchase processes on major search engines, but they’re actually deciding on the specific product that they want, the vendor they want it from and the price that they’re comfortable paying for it by performing searches on alternative sites.

comScore data also shows that searches on alternative search websites can be up to 14% greater in length than searches on traditional search engines.

Because of this, brands can reach deeper into funnel stages through alternative search, as the more specific consumers are with their search, the easier it is to target those consumers that are in purchase mode.

This also means that alternative search properties are collecting higher quality search data. (You can read more details around alternative search behaviors in a new report from my company, Magnetic, Searching Beyond Search: Life Beyond the Googleplex.)

To target people that have an idea of what they want, or people who have already made up their mind about a purchase, using data from Google, Yahoo! or Bing is the right approach.

However, in order to target people who are actively comparing your product against your competitors’ products (and to then help them choose your product over all others), marketers should consider data that comes from alternative search sites.

These “alternative” sources of data can drive new marketing strategies and provide brand marketers with a new mindset when it comes to whom they want to reach.

Opinions expressed in this article are those of the guest author and not necessarily Search Engine Land. Staff authors are listed here.

Related stories

New on Search Engine Land